如果你也在 怎样代写统计推断Statistical inference这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。统计推断statistics interference可用于机械零件的尺寸计算,确定所施加的载荷何时超过结构的强度,以及在许多其他情况下。这种类型的分析也可以用来估计故障的概率或故障的频率。

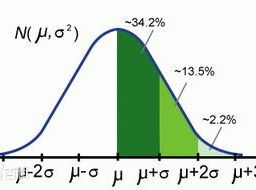

统计推断Statistical inference机械部件通常被设计为精确地配合在一起。例如,如果一个轴被设计成在一个孔中 “滑动配合”,轴必须比孔小一点。(传统的公差可能表明,所有的尺寸都在这些预定的公差之内。然而,对实际生产的过程能力研究可能显示出具有长尾巴的正态分布)。轴和孔的尺寸通常会形成具有一些平均值(算术平均值)和标准差的正态分布。

my-assignmentexpert™ 统计推断Statistical inference作业代写,免费提交作业要求, 满意后付款,成绩80\%以下全额退款,安全省心无顾虑。专业硕 博写手团队,所有订单可靠准时,保证 100% 原创。my-assignmentexpert™, 最高质量的统计推断Statistical inference作业代写,服务覆盖北美、欧洲、澳洲等 国家。 在代写价格方面,考虑到同学们的经济条件,在保障代写质量的前提下,我们为客户提供最合理的价格。 由于统计Statistics作业种类很多,同时其中的大部分作业在字数上都没有具体要求,因此统计推断Statistical inference作业代写的价格不固定。通常在经济学专家查看完作业要求之后会给出报价。作业难度和截止日期对价格也有很大的影响。

想知道您作业确定的价格吗? 免费下单以相关学科的专家能了解具体的要求之后在1-3个小时就提出价格。专家的 报价比上列的价格能便宜好几倍。

my-assignmentexpert™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在统计Statistics作业代写方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的统计推断Statistical inference代写服务。我们的专家在统计Statistics代写方面经验极为丰富,各种统计推断Statistical inference相关的作业也就用不着 说。

我们提供的统计推断Statistical inference及其相关学科的代写,服务范围广, 其中包括但不限于:

统计代写|统计推断作业代写Statistical inference代考|Ancient Greece

The first such cognitive revolution of which we have clear evidence began in ancient Greece around the time of Hesiod and the pre-Socratic philosophers and culminated in the work of Plato. Julian Jaynes (1976) traces the changes through the writings, perhaps spanning several centuries, which are commonly attributed to Homer. The developments in question can be summarized as a shift to interiority, from the concrete to the abstract, and from a participative mode of knowing to a sharp separation between knower and known. There is good reason to suppose that the introduction of writing was primarily responsible. Hellenic culture of about 1000 B.C. appears to have been unusual in being so highly developed while still lacking a system of writing. Greece may have been less rich in clay or papyrus than Sumer or Egypt, but the Cretans had a linear script as early as the seventeenth century B.C. (Diringer, 1968). A more likely reason for the “delay” may be just the success of the splendid alternative developed by the Greeks for the transmission of culture, namely, the oral tradition of epic poetry. The need for some such medium was heightened by the

scattering of the Greeks in the Dorian invasions around the end of the twelfth century B.C. Havelock (1963) shows in some detail how artfully embedded within the narratives were numerous observations on how things were done, from resolving conflicts to mustering a ship’s crew, so that the epics constituted a sort of “tribal encyclopedia.” Their poetic structure, moreover, was designed to facilitate memorization. Acoustic rhythms, for example, were reinforced in various ways during performance by bodily participation.

The date of the invention of the Greek alphabet has been the subject of considerable debate (cf. Diringer, 1968), but reliance on oral recitation of epic narratives persisted for several more centuries in any case. The Greek alphabet had the advantage of being as efficient as any system of writing that ever attained widespread use. It is also remarkable in having been taken over rather directly from the Phoenicians, as an aid to commerce, with the result that the names of the letters were meaningless in the Greek language. It is tempting to speculate that the evident arbitrariness of this connection between spoken and written language facilitated the abstraction of the self from the world. Donald (1991) suggests, however, that the uniqueness of the Greeks lay simply in their having been the first to record their mythic narratives, as opposed to using writing merely for shipping invoices, calendars, genealogical trees, and the like.

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|Medieval Europe

Whenever thoughts of cognitive losses from impending senility threaten to depress us, we can take comfort, if we wish, from the Dark Ages, which remind us that history, even with its Arabs as repositories, is scarcely more secure than ontogenesis from the loss of precious developmental achievements. Radding (1985) discerns already in Augustine’s thought a concreteness that contrasts with Cicero’s, and he goes so far as to suggest that it was the cognitive deterioration of Roman civilization that made it more susceptible to invasions rather than vice versa. In the centuries that followed, the alphabet was not lost, but literacy certainly was, and along with it evidence of a capacity for abstract reasoning. By the sixth century, discourse had degenerated to parataxis; a narrative of a murder by Gregory of Tours-a light of his time-is overwhelmed and obscured by what we would regard as irrelevant details, omitting those we might think important, like the identity or motive of the murderer, all juxtaposed with no visible sense of organization (Radding, 1985).

The end of the early Middle Ages is usually dated from the rediscovery of the Greeks, though Radding thinks certain cognitive developments were necessary before the Greek authors would have made any sense. Writing and geographical dispersion again seem to have been involved in setting the stage for the cognitive revolution which occurred around the eleventh century. Bede, at the turn of the eighth century, had access to two different Latin translations of the Bible; being thus forced to grapple with the issue that the Scriptures were supposed to be God’s exact words entailed some distancing from the text and an attitude of critical reflection. Similarly, the unification of all of central Europe in the Carolingian conquest a century later revealed an unsuspected diversity of religious belief and practice, making it difficult for people to continue in their assumption that they were all following God’s laws. The embarrassing proliferation of conflicting authorities eventually made it necessary for writers to develop arguments in support of their views and to take account of the perspective of their audience or adversary. Dawson (1950) contends that the first such example arose in the eleventh century, from tensions inherent in the concept of the Holy Roman Empire, with the Church as political as well Radding finds a general collapse of traditional authority around the year 1000 (though he does not suggest a connection with the failure of millennial prophecies), with the beginning of the twelfth century marking a new era in Western Europe comparable to the fifth century B.C. in Athens.

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|General Observations

It will be instructive to notice similarities and differences between these two early epistemological discontinuities-culminating in the fifth century B.C. and the twelfth century A.D., after two or three centuries of preparatory developmentsbefore proceeding to that in the seventeenth century.

Either of these could be counted, for its particular culture, as the emergence of self-consciousness (or at least a step in that direction). In ancient Greece, the change was apparent even in language, as in the shift in loci of agency from thumos and phrenes to psyche (J. Jaynes, 1976). In the twelfth century, we see a new selfawareness reflected in the appearance, or reappearance, of phenomena as diverse as guilt and individual portraiture (Berman, 1989). Alternatively, and perhaps a shade more cynically, what I am calling the emergence of self-consciousness could be construed as the emergence of epistemology, an explicit concern with knowledge as no longer taken merely for granted. Both historical transformations also entailed a degree of trauma, inasmuch as the previous pragmatic-intuitive mode of cognition carried an unreflective certainty or assurance which was lost to the vagaries of philosophy. What was furthermore lost with the ascendance of philosophy was, in both cases, the legitimation of carnal knowledge and of participative, ecstatic experience, in particular.

The cardinal difference appears to be the context out of which they arose: The cultural tradition fought by Plato was well established and successful, whereas that confronted by Abelard or Anselm was by comparison mute and unformed. The consequences for subsequent development depend greatly on whether an existing order must be dealt with. The typical, though not logically necessary, response in this case, as Havelock (1963) noted, is the most vehement possible opposition and denunciation. This was the pattern in ancient Greece and in seventeenth-century Europe, and it characteristically engenders deep splits and polarizations throughout the culture. Either mode of change, however, leaves its “shadow” side; Radding (1985) notes that as saints and devils gave way increasingly to natural explanation among the intellectuals of the twelfth century, mysticism and occultism found correspondingly renewed energy.

统计推断学代写

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|ANCIENT GREECE

我们有明确证据的第一次这样的认知革命始于古希腊,大约在赫西奥德和前苏格拉底哲学家的时代,并在柏拉图的工作中达到高潮。朱利安杰恩斯1976通过可能跨越几个世纪的著作来追溯这些变化,这些著作通常归因于荷马。所讨论的发展可以概括为向内在性的转变,从具体到抽象,从参与式的认识模式转变为认识者与已知者之间的明显分离。有充分的理由假设文字的引入是主要责任。公元前 1000 年左右的希腊文化在如此高度发达的同时仍然缺乏书写系统,这似乎是不寻常的。希腊的粘土或纸莎草纸可能不如苏美尔或埃及丰富,但早在公元前 17 世纪,克里特人就有线性文字D一世r一世nG和r,1968. “延迟”的一个更可能的原因可能只是希腊人为文化传播而开发的辉煌替代品的成功,即史诗的口头传统。对一些这样的媒体的需求因

公元前十二世纪末,希腊人在多利安人的入侵中分散开来1963详细地展示了叙事中如何巧妙地嵌入了对事情如何完成的大量观察,从解决冲突到召集船员,因此史诗构成了一种“部落百科全书”。此外,它们的诗意结构旨在促进记忆。例如,声音节奏在表演过程中通过身体参与以各种方式得到加强。

希腊字母的发明日期一直是争论不休的话题CF.D一世r一世nG和r,1968,但无论如何,对史诗叙事的口头朗诵的依赖持续了几个世纪。希腊字母表的优势在于与任何曾被广泛使用的书写系统一样高效。同样值得注意的是,它直接从腓尼基人手中接管,作为对商业的帮助,结果字母的名称在希腊语中毫无意义。很容易推测,口语和书面语言之间这种明显的任意性联系促进了自我与世界的抽象。唐纳德1991然而,这表明希腊人的独特性仅仅在于他们是第一个记录神话故事的人,而不是仅仅将文字用于运输发票、日历、家谱等。

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|MEDIEVAL EUROPE

每当因即将衰老而导致认知丧失的想法威胁到让我们沮丧时,如果我们愿意,我们可以从黑暗时代中得到安慰,这提醒我们,即使以阿拉伯人为宝库,历史也几乎不会比因失去生命而导致的个体发生更安全。宝贵的发展成果。拉丁1985在奥古斯丁的思想中已经看出了与西塞罗的思想形成鲜明对比的具体性,他甚至认为是罗马文明的认知退化使其更容易受到入侵,而不是相反。在随后的几个世纪里,字母表并没有消失,但读写能力肯定是消失了,随之而来的是抽象推理能力的证据。到了六世纪,话语已经退化为并列。图尔的格雷戈里(Gregory of Tours)的谋杀叙事——他的时代之光——被我们认为无关紧要的细节所淹没和遮蔽,省略了我们可能认为重要的那些,比如凶手的身份或动机,所有这些都与不可见的并列组织感R一种dd一世nG,1985.

中世纪早期的结束通常可以追溯到希腊人的重新发现,尽管拉丁认为在希腊作家有任何意义之前,某些认知发展是必要的。写作和地理分散似乎再次为 11 世纪左右发生的认知革命奠定了基础。八世纪之交,贝德获得了两种不同的拉丁语圣经译本。因此,被迫解决圣经应该是上帝的确切话语的问题需要与文本保持一定距离和批判性反思的态度。同样,一个世纪后加洛林王朝征服整个中欧的统一揭示了宗教信仰和实践出人意料的多样性,使人们难以继续假设他们都在遵守上帝的律法。相互矛盾的权威令人尴尬地激增,最终使作家有必要发展论据来支持他们的观点,并考虑到他们的听众或对手的观点。道森1950争辩说,第一个这样的例子出现在 11 世纪,源于神圣罗马帝国概念中固有的紧张关系,教会与政治一样,Radding 发现传统权威在 1000 年左右普遍崩溃吨H这你GHH和d这和sn这吨s你GG和s吨一种C这nn和C吨一世这n在一世吨H吨H和F一种一世一世你r和这F米一世一世一世和nn一世一种一世pr这pH和C一世和s,十二世纪初标志着西欧的一个新时代,可与公元前五世纪的雅典相媲美。

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

注意到这两个早期认识论的不连续性之间的相似和不同将是有益的——在经过两三个世纪的准备发展之后,在公元前五世纪和公元十二世纪达到顶峰,然后在十七世纪继续发展。

就其特定的文化而言,其中任何一个都可以算作自我意识的出现这r一种吨一世和一种s吨一种s吨和p一世n吨H一种吨d一世r和C吨一世这n. 在古希腊,这种变化甚至在语言上也很明显,例如代理位置从 thumos 和 phrenes 到 psyche 的转变Ĵ.Ĵ一种是n和s,1976. 在 12 世纪,我们看到了一种新的自我意识,这种新的自我意识反映在罪恶感和个人肖像画等多种多样的现象的出现或再现中乙和r米一种n,1989. 或者,也许更讽刺的是,我所说的自我意识的出现可以解释为认识论的出现,一种对知识的明确关注,不再仅仅被视为理所当然。这两种历史转变也带来了一定程度的创伤,因为先前的实用-直觉认知模式带有一种未经反思的确定性或保证,这种确定性或保证在哲学的变幻莫测中消失了。在这两种情况下,随着哲学的兴起而失去的是肉体知识的合法化,尤其是参与性的、狂喜的体验。

主要区别似乎是它们产生的背景:柏拉图所反对的文化传统已经确立并取得了成功,而阿伯拉德或安瑟姆所面对的文化传统相比之下是沉默的和未形成的。后续发展的后果很大程度上取决于是否必须处理现有订单。在这种情况下,典型的(虽然不是逻辑上必要的)响应,如 Havelock1963指出,是最激烈的反对和谴责。这是古希腊和 17 世纪欧洲的模式,它典型地在整个文化中造成了深刻的分裂和两极分化。然而,任何一种变革模式都留下了“阴影”的一面。拉丁1985注意到随着圣人和魔鬼越来越多地让位于 12 世纪知识分子的自然解释,神秘主义和神秘主义相应地找到了新的活力。

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考 请认准UprivateTA™. UprivateTA™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。