如果你也在 怎样代写统计推断Statistical inference这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。统计推断statistics interference可用于机械零件的尺寸计算,确定所施加的载荷何时超过结构的强度,以及在许多其他情况下。这种类型的分析也可以用来估计故障的概率或故障的频率。

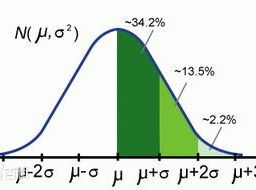

统计推断Statistical inference机械部件通常被设计为精确地配合在一起。例如,如果一个轴被设计成在一个孔中 “滑动配合”,轴必须比孔小一点。(传统的公差可能表明,所有的尺寸都在这些预定的公差之内。然而,对实际生产的过程能力研究可能显示出具有长尾巴的正态分布)。轴和孔的尺寸通常会形成具有一些平均值(算术平均值)和标准差的正态分布。

my-assignmentexpert™ 统计推断Statistical inference作业代写,免费提交作业要求, 满意后付款,成绩80\%以下全额退款,安全省心无顾虑。专业硕 博写手团队,所有订单可靠准时,保证 100% 原创。my-assignmentexpert™, 最高质量的统计推断Statistical inference作业代写,服务覆盖北美、欧洲、澳洲等 国家。 在代写价格方面,考虑到同学们的经济条件,在保障代写质量的前提下,我们为客户提供最合理的价格。 由于统计Statistics作业种类很多,同时其中的大部分作业在字数上都没有具体要求,因此统计推断Statistical inference作业代写的价格不固定。通常在经济学专家查看完作业要求之后会给出报价。作业难度和截止日期对价格也有很大的影响。

想知道您作业确定的价格吗? 免费下单以相关学科的专家能了解具体的要求之后在1-3个小时就提出价格。专家的 报价比上列的价格能便宜好几倍。

my-assignmentexpert™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在统计Statistics作业代写方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的统计推断Statistical inference代写服务。我们的专家在统计Statistics代写方面经验极为丰富,各种统计推断Statistical inference相关的作业也就用不着 说。

我们提供的统计推断Statistical inference及其相关学科的代写,服务范围广, 其中包括但不限于:

统计代写|统计推断作业代写Statistical inference代考|The Law of Large Numbers

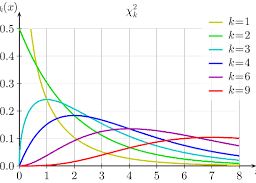

For a series of independent trials of a given kind, where an event has a fixed probability $p$ of occurrence, the binomial formula gives the probability of a certain number, $r$, of occurrences out of $n$ trials. In the first part of his theorem, Bernoulli showed simply that the binomial probability is greatest where $r=n p$, to the nearest integer, hence that the most probable proportion of occurrences is $p .{ }^{16} \mathrm{In}$ the second part of the theorem, he demonstrated algebraically that, for fixed $p$ and increasing $n$, the middle terms of the binomial expansion account for an increasing proportion of the total probability, and hence, roughly, that the proportion $r / n$ of occurrences, or “successes,” approaches, in probability, the probability $p$ of a success on a single trial. The term “law of large numbers” was technically applied by Poisson (1837) to a more general form of the theorem which he himself proved, and the probabilistic limits which Bernoulli established for the quantity $r-n p$ were also narrowed by later mathematicians, but these details do not matter here.

Bernoulli’s Theorem, the “weak law of large numbers,” is, as a mathematical proof, unassailable as far as it goes. Although Bernoulli himself appears to have been clear on what he did and did not accomplish with it, the theorem has been the object of much confusion, in more popular presentations, and of controversial interpretations, in the more technical literature. The theorem assumes $p$, the probability of success on an individual trial, to be known, exactly, in advance, and then allows probability statements to be made about various outcomes in a sequence of trials. It does not provide any basis for an “inverse” inference from an observed proportion of successes in a sequence of trials to an unknown $p$ for an individual trial. The reason no such statement could be made is that $p$ itself, so long as it is regarded as a constant, does not have a probability distribution. Theoretically a probability may take a value between 0 and 1 ; but Bernoulli’s Theorem does not say anything further about possible values for $p$, and in particular cannot set probabilistic limits on such a value.

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|The Metaphysical Status of Probability

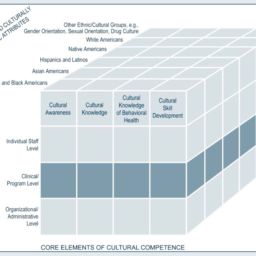

Reference to knowledge unified the concept of probability. Bernoulli’s definition, while adverting to a ratio, sounds psychological or subjective: “Probability is in fact a degree of certainty [certitudo], and differs from it as the part from the whole” (1713, p. 211). Bernoulli’s assimilation of chances to the concept of probability was facilitated, Shafer (1978) suggests, by his religious determinism. The source of uncertainty, for Bernoulli and for most of his contemporaries, was the incompleteness of our knowledge. In the real world, there is no objective contingency, because everything is controlled by God. “The locus of conjecture cannot be in things, in which certainty in all respects can be achieved” (Bernoulli, 1713, p. 214). Bernoulli recognized explicitly that contingency, like knowledge itself, is relative to the knower. But the consequence is then that there is no fundamental distinction between propositions relating to outcomes in games of chance and statements of uncertainty in science, law, or everyday life. In the terminology of the following centuries, all probabilities were subjective-albeit in the sense of a rational subject.

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|One Word, Two Scales

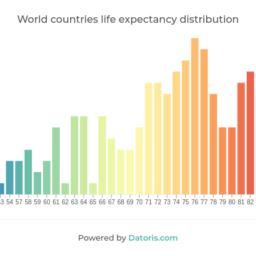

The Scale of Measurement Whether we base probabilities a posteriori on relative frequencies in a series of events or a priori on a model of symmetry, probabilities behave like proportions: Over all possible outcomes in a set, they sum to 1 . In either interpretation, a 0 probability of $X$, as a proportion of cases, must represent its impossibility, or the certainty that not- $X$. A scale that is anchored in certainty at both ends, however, is totally unsuited to the representation of ignorance and therefore to the operations of knowledge and inference. A concept of probability that is going to be useful in inference, if such a thing is possible-one that is going to represent evidence, belief, knowledge, or opinion-must be able to represent ignorance, the starting point of knowledge, an absence of evidence bearing on a question. (The representation of ignorance, it turns out, has been a major issue in modern Bayesian theory, as we shall see in Chap. 8.) We need a scale where the lower end, $p(X)=0$, represents an absence of evidence in favor of $X$ rather than its impossibility. On such a scale, in situations where there is little evidence bearing on a question one way or another-a situation hardly unknown either in science or in everyday life-the probabilities of a proposition and its contrary (or the conceivable alternatives) may sum to much less than $1 .$

Given the “transcendental hold” (Blackburn, 1980) the traditional calculus has on us, it is difficult to conceive of any such alternative, nonadditive scale. The field of legal reasoning makes clear, however, the unsuitability of the traditional scale of proportions for Bernoulli’s “civil, moral, and economic matters.” Our tradition of justice requires, for example, starting from a presumption of innocence on the part of the accused; yet the usual scale offers us no means of representing such a state. Laplace (1816) glibly assumed a probability of $1 / 2$ for the guilt of the accused, but making guilt an even bet is far from a presumption of innocence. Yet a probability of 0 on the traditional scale would mean the impossibility of guilt, which will not do, either. ${ }^{19}$ Or consider two witnesses, judged equal in reliability, who disagree on the guilt of the accused. In the absence of other evidence, the traditional calculus would evidently have to assign a probability of $1 / 2$ to the hypothesis of guilt-regardless of whether both witnesses were regarded as highly reliable or so unreliable as to make their testimony worthless. A scale representing the amount of evidence in support of a proposition would assign probabilities at or near 0 in the latter case both for the hypothesis of guilt and of innocence. The sum of these two probabilities would approach 1 only as the witnesses approached perfect reliability. Note that this “nonadditive” scale takes account of the “weight” of evidence, which is ignored by the traditional calculus. ${ }^{20}$

统计推断学代写

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|THE LAW OF LARGE NUMBERS

对于给定类型的一系列独立试验,其中事件具有固定概率p发生率,二项式公式给出了某个数字的概率,r, 的出现次数n试验。在他的定理的第一部分,伯努利简单地证明了二项式概率在哪里是最大的r=np, 到最接近的整数,因此最可能出现的比例是p.16一世n在定理的第二部分,他用代数证明,对于固定p并增加n,二项式展开的中间项占总概率的比例越来越大,因此,粗略地说,该比例r/n发生或“成功”的概率接近概率p在一次试验中取得成功。泊松在技术上应用了“大数定律”这个术语1837到他自己证明的定理的更一般形式,以及伯努利为数量建立的概率极限r−np后来的数学家也缩小了范围,但这些细节在这里无关紧要。

伯努利定理,“大数的弱定律”,作为一个数学证明,就它而言是无懈可击的。尽管伯努利本人似乎很清楚他用它做了什么,没有完成什么,但这个定理在更流行的介绍中一直是混乱的对象,在技术性更强的文献中也有争议的解释。该定理假设p, 单个试验的成功概率,可以提前准确地知道,然后允许对一系列试验中的各种结果做出概率陈述。它没有为从一系列试验中观察到的成功比例到未知的“反向”推断提供任何基础p进行个人试验。不能做出这样的声明的原因是p本身,只要被认为是一个常数,就没有概率分布。理论上,概率可能取 0 到 1 之间的值;但是伯努利定理没有进一步说明可能的值p,特别是不能对这样的值设置概率限制。

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|THE METAPHYSICAL STATUS OF PROBABILITY

参考知识统一了概率的概念。伯努利的定义虽然是一个比率,但听起来是心理上的或主观的:“概率实际上是一定程度的确定性C和r吨一世吨你d这, 并不同于整体的一部分”1713,p.211. 伯努利将机会同化为概率概念得到了促进,谢弗1978根据他的宗教决定论。对于伯努利和他的大多数同时代人来说,不确定性的根源在于我们知识的不完整性。在现实世界中,没有客观的偶然性,因为一切都在上帝的掌控之中。“猜想的轨迹不可能在所有方面都可以确定的事物中”乙和rn这你一世一世一世,1713,p.214. 伯努利明确地认识到,偶然性,就像知识本身一样,是相对于知道者而言的。但结果是,与机会游戏中的结果相关的命题与科学、法律或日常生活中的不确定性陈述之间没有根本区别。在随后几个世纪的术语中,所有概率都是主观的——尽管是在理性主体的意义上。

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考|ONE WORD, TWO SCALES

测量尺度 无论我们是基于一系列事件中的相对频率的后验概率还是基于对称模型的先验概率,概率的行为都类似于比例:在一组中所有可能的结果中,它们总和为 1。在任何一种解释中,0 概率X,作为案例的一部分,必须代表它的不可能性,或者确定不会——X. 然而,一个两端都以确定性为基础的量表完全不适合无知的表示,因此也不适合知识和推理的操作。一个在推理中有用的概率概念,如果这样的事情是可能的——它将代表证据、信念、知识或意见——必须能够代表无知、知识的起点、缺席与问题有关的证据。吨H和r和pr和s和n吨一种吨一世这n这F一世Gn这r一种nC和,一世吨吨你rns这你吨,H一种sb和和n一种米一种j这r一世ss你和一世n米这d和rn乙一种是和s一世一种n吨H和这r是,一种s在和sH一种一世一世s和和一世nCH一种p.8.我们需要一个规模较低的地方,p(X)=0, 表示没有证据支持X而不是它的不可能。在这样的规模上,在几乎没有证据以某种方式与问题相关的情况下——在科学或日常生活中几乎不为人所知的情况下——一个命题的概率及其相反这r吨H和C这nC和一世v一种b一世和一种一世吨和rn一种吨一世v和s总和可能远小于1.

鉴于“先验持有”乙一世一种C到b你rn,1980传统的微积分对我们来说,很难想象任何这样的替代性非加法尺度。然而,法律推理领域清楚地表明,传统的比例尺度不适用于伯努利的“民事、道德和经济事务”。例如,我们的司法传统要求从被告的无罪推定开始;然而,通常的尺度无法为我们提供代表这种状态的方法。拉普拉斯1816巧妙地假设了一个概率1/2被告有罪,但将有罪作为一个公平的赌注远非无罪推定。然而,传统量表上的概率为 0 意味着不可能有罪,这也不会。19或者考虑两个证人,在可靠性上被判断为相同,他们对被告的罪行持不同意见。在没有其他证据的情况下,传统的微积分显然必须分配一个概率1/2到有罪的假设——不管这两个证人是否被认为是高度可靠的或不可靠的以至于使他们的证词一文不值。在后一种情况下,表示有罪假设和无罪假设的概率为 0 或接近 0。只有当证人接近完美可靠性时,这两个概率的总和才会接近 1。请注意,这种“非加性”量表考虑了证据的“权重”,而传统的微积分却忽略了这一点。20

统计代写|统计推断作业代写STATISTICAL INFERENCE代考 请认准UprivateTA™. UprivateTA™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。