微积分note Absolute Convergence

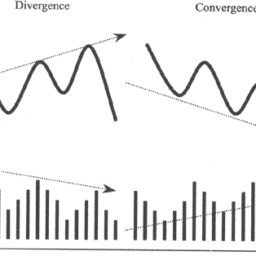

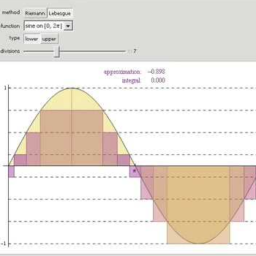

5.4.1 Convergence Because of Cancellation

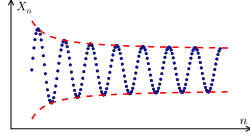

So far, the tests for convergence have been applied to non negative terms only. Sometimes, a series converges, not because the terms of the series get small fast enough, but because of cancellation taking place between positive and negative terms. A discussion of this involves some simple slgebra.

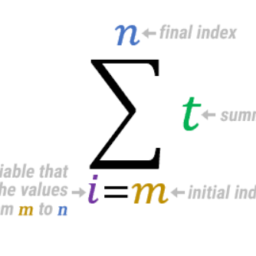

Let $\left{a_{n}\right}$ and $\left{b_{n}\right}$ be sequences and let

$$

A_{n} \equiv \sum_{k=1}^{n} a_{k}, A_{-1} \equiv A_{0} \equiv 0 .

$$

85

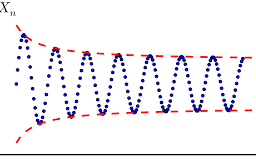

5.4. MORE T Then if $p0$ for all $n, a$ series of the form $\sum_{k}(-1)^{k} b_{k}$ or $\sum_{k}(-1)^{k-1} b_{k}$ is known as an alternating series. The following corollary is known as the alternating series test. Corollary $5.4 .3$ (alternating series test) If lim $_{n \rightarrow \infty} b_{n}=0$, with $b_{n} \geq b_{n+1}$, then $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}$ converges.

The following corollary is known as the alternating series test.

Corollary 5.4.3 (alternating series test) If $\lim {n \rightarrow \infty} b{n}=0$, with $b_{n} \geq b_{n+1}$, then $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}$ converges.

Proof: Let $a_{n}=(-1)^{n}$. Then the partial sums of $\sum_{n} a_{n}$ are bounded and so Theorem 5.4.1 applies.

In the situation of Corollary 5.4.3 there is a convenient error estimate available.

Theorem $5.4 .4$ Let $b_{n}>0$ for all $n$ such that $b_{n} \geq b_{n+1}$ for all $n$ and $\lim {n \rightarrow \infty} b{n}=$ 0 and consider either $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}$ or $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n-1} b_{n}$. Then

$$

\begin{array}{r}

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}-\sum_{n=1}^{N}(-1)^{n} b_{n}\right| \leq\left|b_{N+1}\right|, \

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n-1} b_{n}-\sum_{n=1}^{N}(-1)^{n-1} b_{n}\right| \leq\left|b_{N+1}\right|

\end{array}

$$

See Problem $\square$ on Page 92 for an outline of the proof of this theorem along with another way to prove the alternating series test.

Example 5.4.5 How many terms must I take in the sum, $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1}$ to be closer than $\frac{1}{10}$ to $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1} ?$

CHAPTER 5. INFINITE SERIES OF NUMBERS

86

From Theorem 5.4.4. I need to find $n$ such that $\frac{1}{n^{2}+1} \leq \frac{1}{10}$ and then $n-1$ is the desired value. Thus $n=3$ and so

$$

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1}-\sum_{n=1}^{2}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1}\right| \leq \frac{1}{10}

$$

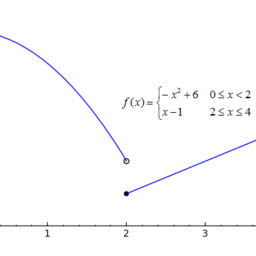

Definition $5.4 .6$ A series $\sum a_{n}$ is said to converge absolutely if $\sum\left|a_{n}\right|$ converges. It is said to converge conditionally if $\sum\left|a_{n}\right|$ fails to converge but $\sum a_{n}$ converges.

Thus the alternating series or more general Dirichlet test can determine convergence of series which converge conditionally.

5.4.2 Ratio And Root Tests

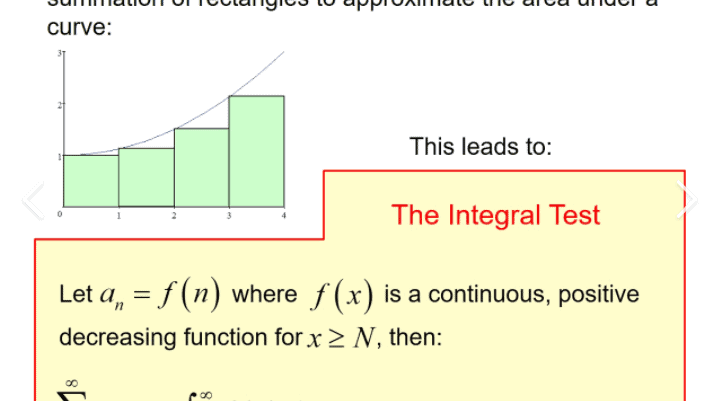

A favorite test for convergence is the ratio test. This is discussed next. It is at the other extreme from the slternating series test, being completely oblivious to any sort of cancellation. It only gives absolute convergence or spectacular divergence.

Theorem $5.4 .7$ Suppose $\left|a_{n}\right|>0$ for all $n$ and suppose

$$

\lim {n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\left|a{n+1}\right|}{\left|a_{n}\right|}=r

$$

Then

$$

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{n}\left{\begin{array}{l}

\text { diverges if } r>1 \

\text { converges absolutely if } r<1 \\ \text { test fails if } r=1 \end{array}\right. $$ Proof: Suppose $r<1$. Then there exists $n_{1}$ such that if $n \geq n_{1}$, then $$ 0<\left|\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_{n}}\right|n$, then $\left|a_{m}\right|1$, then $5.8$ can be turned around for some $R>1$. Showing $\lim {n \rightarrow \infty}\left|a{n}\right|=\infty$. Since the $n^{\text {th }}$ term fails to converge to 0 , it follows the series diverges.

To soe the test fails if $r=1$, consider $\sum n^{-1}$ and $\sum n^{-2}$. The first series diverges while the second one converges but in both cases, $r=1$. (Be sure to check this last claim.)

The ratio test is very useful for many different examples but it is somewhat unsatisfactory mathematically. One reason for this is the assumption that $a_{n} \neq 0$, necessitated by the need to divide by $a_{n}$, and the other reason is the possibility that the limit might not exist. The next test, called the root test removes both of these objections. Before presenting this test, it is necessary to first prove the existence of the $p^{\text {th }}$ root of any positive number. This was shown earlier in Theorem $2.11 .2$ but the following lemma gives an easier treatment of this issue based on theorems about sequences.

5.4. MORE TESTS FOR CONVERGENCE

87

Lemma $5.4 .8$ Let $\alpha>0$ be any nonnegative number and let $p \in \mathbb{N}$. Then $\alpha^{1 / p}$ exists. This is the unique positive number which when raised to the $p^{\text {th }}$ power gives $\alpha$.

Proof: Consider the function $f(x) \equiv x^{p}-\alpha$. Then there exists $b_{1}$ such that $f\left(b_{1}\right)>0$ and $a_{1}$ such that $f\left(a_{1}\right)<0$. (Why?) Now cut the interval $\left[a_{1}, b_{1}\right]$ into two closed intervals of equal length. Let $\left[a_{2}, b_{2}\right]$ be one of these which has $f\left(a_{2}\right) f\left(b_{2}\right) \leq 0$. Now do for $\left[a_{2}, b_{2}\right]$ the same thing which was done to get $\left[a_{2}, b_{2}\right]$ from $\left[a_{1}, b_{1}\right]$. Continue this way obtaining a sequence of nested intervals $\left[a_{k}, b_{k}\right]$ with the property that

$$

b_{k}-a_{k}=2^{1-k}\left(b_{1}-a_{1}\right) \text {. }

$$

By the nested interval theorem, there exists a unique point $x$ in all these intervals. By Theorem 4.4.8

$$

f\left(a_{k}\right) \rightarrow f(x), f\left(b_{k}\right) \rightarrow f(x) .

$$

5.4.1 对消收敛

到目前为止,收敛性测试仅适用于非负项。有时,级数收敛,不是因为级数的项变小得足够快,而是因为正项和负项之间发生抵消。对此的讨论涉及一些简单的代数。

令 $\left{a_{n}\right}$ 和 $\left{b_{n}\right}$ 为序列并让

$$

A_{n} \equiv \sum_{k=1}^{n} a_{k}, A_{-1} \equiv A_{0} \equiv 0 。

$$

85

5.4.更多 T 那么如果 $p0$ 对所有 $n,形式为 $\sum_{k}(-1)^{k} b_{k}$ 或 $\sum_{k 的 $ 系列}(-1)^{k-1} b_{k}$ 被称为交替级数。以下推论称为交替串联测试。推论 $5.4 .3$ (交替系列测试) 如果 lim $_{n \rightarrow \infty} b_{n}=0$, $b_{n} \geq b_{n+1}$, 那么 $\sum_{ n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}$ 收敛。

以下推论称为交替串联测试。

推论 5.4.3(交替系列测试)如果 $\lim {n \rightarrow \infty} b{n}=0$,其中 $b_{n} \geq b_{n+1}$,则 $\sum_{ n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}$ 收敛。

证明:令$a_{n}=(-1)^{n}$。然后 $\sum_{n} a_{n}$ 的部分和是有界的,因此适用定理 5.4.1。

在推论 5.4.3 的情况下,有一个方便的误差估计可用。

定理 $5.4 .4$ 令 $b_{n}>0$ 对于所有 $n$ 使得 $b_{n} \geq b_{n+1}$ 对于所有 $n$ 和 $\lim {n \rightarrow \ infty} b{n}=$ 0 并考虑 $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}$ 或 $\sum_{n-1}^{\ infty}(-1)^{n-1} b_{n}$。然后

$$

\开始{数组}{r}

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} b_{n}-\sum_{n=1}^{N}(-1)^{n} b_{n }\对| \leq\left|b_{N+1}\right|, \

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n-1} b_{n}-\sum_{n=1}^{N}(-1)^{n-1 } b_{n}\右| \leq\left|b_{N+1}\right|

\结束{数组}

$$

请参阅第 92 页上的问题 $\square$ 以了解该定理的证明大纲以及证明交替级数检验的另一种方法。

例 5.4.5 我必须在总和中取多少项,$\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1}$比 $\frac{1}{10}$ 更接近 $\sum_{n-1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1} ?$

第 5 章 无限数列

86

从定理 5.4.4。我需要找到 $n$ 使得 $\frac{1}{n^{2}+1} \leq \frac{1}{10}$ 然后 $n-1$ 是所需的值。因此 $n=3$ 等等

$$

\left|\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}(-1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1}-\sum_{n=1}^{2}( -1)^{n} \frac{1}{n^{2}+1}\right| \leq \frac{1}{10}

$$

定义 $5.4 .6$ 如果 $\sum\left|a_{n}\right|$ 收敛,则称级数 $\sum a_{n}$ 绝对收敛。如果 $\sum\left|a_{n}\right|$ 未能收敛,但 $\sum a_{n}$ 收敛,则称为条件收敛。

因此,交替级数或更一般的 Dirichlet 检验可以确定有条件收敛的级数的收敛性。

5.4.2 比率和根检验

最喜欢的收敛测试是比率测试。这将在接下来讨论。它与激烈的系列测试处于另一个极端,完全没有注意到任何形式的取消。它只会给出绝对的收敛或惊人的分歧。

定理 $5.4 .7$ 假设 $\left|a_{n}\right|>0$ 对于所有 $n$ 并假设

$$

\lim {n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{\left|a{n+1}\right|}{\left|a_{n}\right|}=r

$$

然后

$$

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{n}\left{\begin{array}{l}

\text { 如果 } r>1 则发散 \

\text { 如果 } r<1 \ 绝对收敛

\text { 如果 } r=1 测试失败

\end{数组}\对。

$$

证明:假设$r<1$。那么存在 $n_{1}$ 使得如果 $n \geq n_{1}$,那么

$$

0<\left|\frac{a_{n+1}}{a_{n}}\right|<R

$$

其中$r<R<1$。然后

$$

\left|a_{n+1}\right|<R\left|a_{n}\right|

$$

对于所有这样的$n$。所以,

$$

\left|a_{n_{1}+\mathrm{p}}\right|<R\left|a_{n_{1}+p-1}\right|<R^{2}\left|a_{n_ {1}+\mathrm{p}-2}\right|<\ldots<R^{p}\left|a_{n_{

微积分note Integer Multiples of Irrational Numbers 请认准UprivateTA™. UprivateTA™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。