统计代写| Definition of expectationstat代写

统计代考

4.1 Definition of expectation

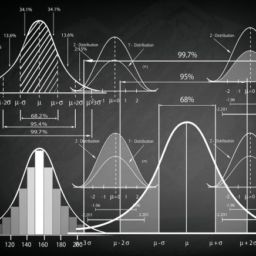

In the previous chapter, we introduced the distribution of a random variable, which gives us full information about the probability that the r.v. will fall into any particular set. For example, we can say how likely it is that the r.v. will exceed 1000, that it will equal 5 , or that it will be in the interval $[0,7]$. It can be unwieldy to manage so many probabilities though, so often we want just one number summarizing the “average” value of the r.v.

There are several senses in which the word “average” is used, but by far the most commonly used is the mean of an r.v., also known as its expected value. In addition, much of statistics is about understanding variability in the world, so it is often important to know how “spread out” the distribution is; we will formalize this with the concepts of variance and standard deviation. As we’ll see, variance and standard deviation are defined in terms of expecte far beyond just computing averages.

Given a list of numbers $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$, the familiar way to average them is to add them up and divide by $n$. This is called the arithmetic mean, and is defined by

$$

\bar{x}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} x_{j} .

$$

More generally, we can define a weighted mean of $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}$ as

$$

\text { weighted-mean }(x)=\sum_{j=1}^{n} x_{j} p_{j},

$$

where the weights $p_{1}, \ldots, p_{n}$ are pre-specified nonnegative numbers that add up to 1 (so the unweighted mean $\bar{x}$ is obtained when $p_{j}=1 / n$ for all $j$ ).

The definition of expectation for a discrete r.v. is inspired by the weighted mean of a list of numbers, with weights given by probabilities.

Definition 4.1.1 (Expectation of a discrete r.v.). The expected value (also called the expectation or mean) of a discrete r.v. $X$ whose distinct possible values are

149

150

$x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots$ is defined by

$$

E(X)=\sum_{j=1}^{\infty} x_{j} P\left(X=x_{j}\right)

$$

If the support is finite, then this is replaced by a finite sum. We can also write

$$

E(X)=\sum_{x} \underbrace{x}{\text {value }} \underbrace{P(X=x)}{\mathrm{PMF} \text { at } x}

$$

where the sum is over the support of $X$ (in any case, $x P(X=x)$ is 0 for any $x$ not in the support). The expectation is undefined if $\sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\left|x_{j}\right| P\left(X=x_{j}\right)$ diverges, since then the series for $E(X)$ diverges or its value depends on the order in which the $x_{j}$ are listed.

In words, the expected value of $X$ is a weighted average of the possible values that $X$ can take on, weighted by their probabilities. Let’s check that the definition makes sense in a few simple examples:

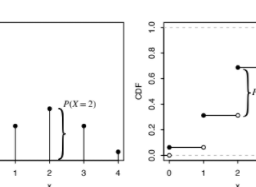

- Let $X$ be the result of rolling a fair 6-sided die, so $X$ takes on the values $1,2,3,4,5,6$, with equal probabilities. Intuitively, we should be able to get the average by adding up these values and dividing by 6 . Using the definition, the expected value is

$$

E(X)=\frac{1}{6}(1+2+\cdots+6)=3.5

$$

as we expected. Note that $X$ never equals its mean in this example. This is similar to the fact that the average number of children per household in some country could be $1.8$, but that doesn’t mean that a typical household has $1.8$ children!

$2 .$

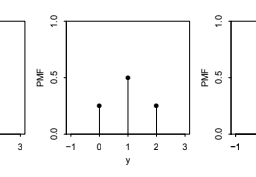

Let $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(p)$ and $q=1-p$. Then

$$

E(X)=1 p+0 q=p

$$

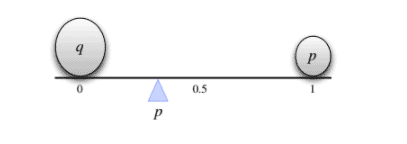

which makes sense intuitively since it is between the two possible values of $X$, compromising between 0 and 1 based on how likely each is. This is illustrated in Figure $4.1$ for a case with $p<1 / 2$ : two pebbles are being balanced on a seesaw. For the seesaw to balance, the fulcrum (shown as triangle) must be at $p$, which in physics terms is the center of mass.

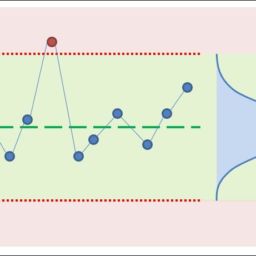

The frequentist interpretation would be to consider a large number of independent Bernoulli trials, each with probability $p$ of success. Writing 1 for “success” and 0 for “failure”, in the long run we would expect to have data consisting of a list of numbers where the proportion of 1’s is very

3.-Let X have 3 distinct poseible values, a $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \mathrm{~ w i t h ~ p r o b a b i l i t i e s ~ p}$ - Let $X$ have 3 distinct possible values, $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}$, with probabilities $p_{1}, p_{2}, p_{3}$, respectively. Imagine running a simulation where $n$ independent draws

统计代考

4.1 期望的定义

在上一章中,我们介绍了随机变量的分布,它为我们提供了关于 r.v.将落入任何特定的集合。例如,我们可以说 r.v. 的可能性有多大。将超过 1000,等于 5,或者在区间 $[0,7]$ 内。但是,管理这么多概率可能很笨拙,所以我们通常只需要一个数字来总结 r.v. 的“平均”值。

使用“平均值”一词有多种含义,但到目前为止,最常用的是 r.v. 的平均值,也称为期望值。此外,许多统计数据都是关于了解世界的可变性,因此了解分布的“分散”程度通常很重要;我们将用方差和标准差的概念将其形式化。正如我们将看到的,方差和标准差是根据预期定义的,远远超出了计算平均值。

给定一个数字列表 $x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}$,熟悉的平均方法是将它们相加并除以 $n$。这称为算术平均值,定义为

$$

\bar{x}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} x_{j} 。

$$

更一般地,我们可以将 $x_{1}, \ldots, x_{n}$ 的加权平均值定义为

$$

\text { 加权平均 }(x)=\sum_{j=1}^{n} x_{j} p_{j},

$$

其中权重 $p_{1}、\ldots、p_{n}$ 是预先指定的非负数,加起来为 1(因此当 $p_{j}=1 时获得未加权平均值 $\bar{x}$ / n$ 为所有 $j$ )。

离散 r.v. 的期望定义受到数字列表的加权平均值的启发,权重由概率给出。

定义 4.1.1(离散 r.v. 的预期)。离散 r.v. 的期望值(也称为期望值或平均值)。 $X$,其不同的可能值为

149

150

$x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots$ 定义为

$$

E(X)=\sum_{j=1}^{\infty} x_{j} P\left(X=x_{j}\right)

$$

如果支持是有限的,则将其替换为有限和。我们也可以写

$$

E(X)=\sum_{x} \underbrace{x}{\text {value }} \underbrace{P(X=x)}{\mathrm{PMF} \text { at } x}

$$

其中总和超过了 $X$ 的支持(在任何情况下,对于任何不在支持中的 $x$,$x P(X=x)$ 都是 0)。如果 $\sum_{j=1}^{\infty}\left|x_{j}\right| 则期望未定义P\left(X=x_{j}\right)$ 发散,从那时起 $E(X)$ 的级数发散或其值取决于 $x_{j}$ 的列出顺序。

换句话说,$X$ 的期望值是 $X$ 可以采用的可能值的加权平均值,由它们的概率加权。让我们通过几个简单的例子来检查定义是否有意义:

- 假设 $X$ 是掷出一个公平的 6 面骰子的结果,因此 $X$ 取值 $1,2,3,4,5,6$,概率相等。直观地说,我们应该能够通过将这些值相加并除以 6 来获得平均值。使用定义,期望值为

$$

E(X)=\frac{1}{6}(1+2+\cdots+6)=3.5

$$

正如我们所料。请注意,在此示例中,$X$ 永远不会等于它的平均值。这类似于某些国家/地区每户家庭的平均儿童数量可能是 1.8 美元,但这并不意味着一个典型的家庭有 1.8 美元的孩子!

$2 .$

令 $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(p)$ 和 $q=1-p$。然后

$$

E(X)=1 p+0 q=p

$$

这在直觉上是有道理的,因为它介于 $X$ 的两个可能值之间,根据每个值的可能性在 0 和 1 之间进行折衷。图 $4.1$ 说明了 $p<1 / 2$ 的情况:两颗鹅卵石在跷跷板上保持平衡。为了使跷跷板平衡,支点(显示为三角形)必须位于 $p$,在物理学术语中是质心。

频率论者的解释是考虑大量独立的伯努利试验,每个试验的成功概率为 $p$。写 1 表示“成功”,写 0 表示“失败”,从长远来看,我们希望有一个由数字列表组成的数据,其中 1 的比例非常

3.-让 X 有 3 个不同的可能值,a $a_{1}, a_{2}, a_{3}, \mathrm{~ w i t h ~ p r o b a b i l i t i e s ~ p}$ - 令 $X$ 有 3 个不同的可能值,$a_{1}、a_{2}、a_{3}$,概率分别为 $p_{1}、p_{2}、p_{3}$。想象一下运行一个模拟,其中 $n$ 独立绘制

R语言代写

统计代写|SAMPLE SPACES AND PEBBLE WORLD stat 代写 请认准UprivateTA™. UprivateTA™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。