统计代写| Bernoulli and Binomial stat代写

统计代考

3.3 Bernoulli and Binomial

Some distributions are so ubiquitous in probability and statistics that they have their own names. We will introduce these named distributions throughout the book, starting with a very simple but useful case: an r.v. that can take on only two possible values, 0 and $1 .$

Definition 3.3.1 (Bernoulli distribution). An r.v. $X$ is said to have the Bernoulli distribution with parameter $p$ if $P(X=1)=p$ and $P(X=0)=1-p$, where $0<p<1$. We write this as $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(p)$. The symbol $\sim$ is read “is distributed as”.

Any r.v. whose possible values are 0 and 1 has a $\operatorname{Bern}(p)$ distribution, with $p$ the probability of the r.v. equaling 1 . This number $p$ in $\operatorname{Bern}(p)$ is called the parameter of the distribution; it determines which specific Bernoulli distribution we have. Thus there is not just one Bernoulli distribution, but rather a family of Bernoulli distributions, indexed by $p$. For example, if $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(1 / 3)$, it would be correct but both say its name (Bernoulli) and its parameter value $(1 / 3)$, which is the point of the notation $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(1 / 3)$.

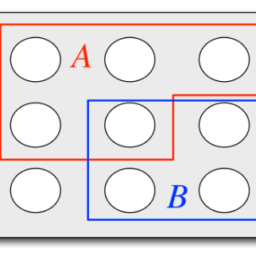

Any event has a Bernoulli r.v. that is naturally associated with it, equal to 1 if the event happens and 0 otherwise. This is called the indicator random variable of the event; we will see that such r.v.s are extremely useful.

Definition 3.3.2 (Indicator random variable). The indicator random variable of an event $A$ is the r.v. which equals 1 if $A$ occurs and 0 otherwise. We will denote the indicator r.v. of $A$ by $I_{A}$ or $I(A)$. Note that $I_{A} \sim \operatorname{Bern}(p)$ with $p=P(A)$.

We often imagine Bernoulli r.v.s using coin tosses, but this is just convenient language for discussing the following general story.

Story 3.3.3 (Bernoulli trial). An experiment that can result in either a “success” or a “failure” (but not both) is called a Bernoulli trial. A Bernoulli random variable can be thought of as the indicator of success in a Bernoulli trial: it equals 1 if success occurs and 0 if failure occurs in the trial.

Because of this story, the parameter $p$ is often called the success probability of the $\operatorname{Bern}(p)$ distribution. Once we start thinking about Bernoulli trials, it’s hard not to start thinking about what happens when we have more than one trial.

Story 3.3.4 (Binomial distribution). Suppose that $n$ independent Bernoulli trials are performed, each with the same success probability $p$. Let $X$ be the number of successes. The distribution of $X$ is called the Binomial distribution with parameters $n$ and $p$. We write $X \sim \operatorname{Bin}(n, p)$ to mean that $X$ has the Binomial distribution vith parameters nond $p$, where $n$ is a positive integer and $0<p<1$

113

andom en ables and their distributions about the type of experiment that could give rise to a random variable with a Binomial distribution. The most famous distributions in statistics all have stories which explain why they are so often used as models for data, or as the building blocks for more complicated distributions.

Thinking about the named distributions first and foremost in terms of their stories has many benefits. It facilitates pattern recognition, allowing us to see when two problems are essentially identical in structure; it often leads to cleaner solutions that avoid PMF calculations altogether; and it helps us understand how the named distributions are connected to one another. Here it is clear that Bern $(p)$ is the same distribution as Bin $(1, p)$ : the Bernoulli is a special case of the Binomial.

Using the story definition of the Binomial, let’s find its PMF.

Theorem $3.3 .5$ (Binomial PMF). If $X \sim \operatorname{Bin}(n, p)$, then the PMF of $X$ is

$P(X=k)=\left(\begin{array}{l}n \ k\end{array}\right) p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}$

for $k=0,1, \ldots, n$ (and $P(X=k)=0$ otherwise).

3.3.6. To save writing, it is often left implicit that a PMF is zero wherever it is not specified to be nonzero, but in any case it is important to understand what the support of a random variable is, and good practice to check that PMFs are valid. If two discrete r.v.s have the same PMF, then they also must have the same support. So we sometimes refer to the support of a discrete distribution; this is the support of any r.v. with that distribution.

Proof. An experiment consisting of $n$ independent Bernoulli trials produces a sequence of successes and failures. The probability of any specific sequence of $k$ successes and $n-k$ failures is $p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}$. There are $\left(\begin{array}{l}n \ k\end{array}\right)$ such sequences, since we just need to select where the successes are. Therefore, letting $X$ be the number of successes,

$$

P(X=k)=\left(\begin{array}{l}

n \

k

\end{array}\right) p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}

$$

for $k=0,1, \ldots, n$, and $P(X=k)=0$ otherwise. This is a valid PMF because it is

nonnegative and it sums to 1 by the binomial theorem.

$$

P(X=k)=\left(\begin{array}{l}

n \

k

\end{array}\right) p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}

$$

for $k=0,1, \ldots, n$, and $P(X=k)=0$ otherwise. This is a valid PMF because it is nonnegative and it sums to 1 by the binomial theorem.

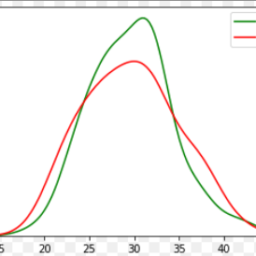

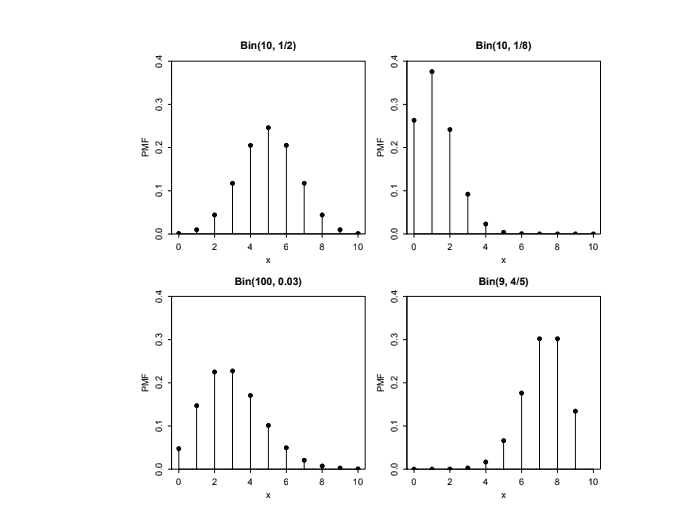

Figure $3.6$ shows plots of the Binomial PMF for various values of $n$ and $p$. Note that the PMF of the Bin $(10,1 / 2)$ distribution is symmetric about 5 , but when the success probability is not $1 / 2$, the PMF is skewed. For a fixed number of trials $n, X$ tends to be larger when the success probability is high and lower when the success probability is low, as we would expect from the story of the Binomial distribution. Also recall that in any PMF plot, the sum of the heights of the vertical bars must be 1 .

We’ve used Story $3.3 .4$ to find the $\operatorname{Bin}(n, p) \operatorname{PMF}$. The story also gives us a straightforward proof of the fact that if $X$ is Binomial, then $n-X$ is also Binomial.

统计代考

3.3 伯努利和二项式

一些分布在概率和统计中无处不在,以至于它们有自己的名字。我们将在整本书中介绍这些命名分布,从一个非常简单但有用的案例开始:一个 r.v.只能取两个可能的值, 0 和 $1 .$

定义 3.3.1(伯努利分布)。房车如果 $P(X=1)=p$ 和 $P(X=0)=1-p$,则 $X$ 具有参数 $p$ 的伯努利分布,其中 $0<p<1$。我们把它写成 $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(p)$。符号 $\sim$ 读作“分发为”。

任何房车其可能值为 0 和 1 具有 $\operatorname{Bern}(p)$ 分布,其中 $p$ 是 r.v. 的概率。等于 1 。 $\operatorname{Bern}(p)$ 中的这个数 $p$ 称为分布的参数;它决定了我们拥有哪种特定的伯努利分布。因此,不仅存在一个伯努利分布,而是一系列伯努利分布,以 $p$ 为索引。例如,如果 $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(1 / 3)$,它会是正确的,但都说它的名字 (Bernoulli) 和它的参数值 $(1 / 3)$,这是符号 $X \sim \operatorname{Bern}(1 / 3)$。

任何事件都有伯努利 r.v.与它自然相关联,如果事件发生则等于 1,否则等于 0。这称为事件的指标随机变量;我们将看到这样的 r.v.s 非常有用。

定义 3.3.2(指标随机变量)。事件 $A$ 的指标随机变量是 r.v。如果 $A$ 出现则等于 1,否则为 0。我们将表示指标 r.v。 $A$ 由 $I_{A}$ 或 $I(A)$。注意 $I_{A} \sim \operatorname{Bern}(p)$ 与 $p=P(A)$。

我们经常想象 Bernoulli r.v.s 使用抛硬币,但这只是讨论以下一般故事的方便语言。

故事 3.3.3(伯努利试验)。可能导致“成功”或“失败”(但不是两者)的实验称为伯努利试验。伯努利随机变量可以被认为是伯努利试验中成功的指标:如果成功则等于 1,如果试验失败则等于 0。

由于这个故事,参数 $p$ 通常被称为 $\operatorname{Bern}(p)$ 分布的成功概率。一旦我们开始考虑伯努利试验,就很难不开始考虑当我们进行不止一次试验时会发生什么。

故事 3.3.4(二项分布)。假设进行了 $n$ 个独立的伯努利试验,每个试验都具有相同的成功概率 $p$。设 $X$ 为成功次数。 $X$ 的分布称为具有参数 $n$ 和 $p$ 的二项式分布。我们写 $X \sim \operatorname{Bin}(n, p)$ 来表示 $X$ 具有带参数 nond $p$ 的二项分布,其中 $n$ 是一个正整数并且 $0<p<1$

113

关于可能产生具有二项式分布的随机变量的实验类型的随机变量及其分布。统计学中最著名的分布都有故事,解释了为什么它们经常被用作数据模型,或者作为更复杂分布的构建块。

首先根据它们的故事来考虑命名的发行版有很多好处。它有助于模式识别,让我们能够看到两个问题在结构上基本相同的情况;它通常会导致更清洁的解决方案,完全避免 PMF 计算;它可以帮助我们理解命名的分布是如何相互连接的。这里很明显 Bern $(p)$ 与 Bin $(1, p)$ 是相同的分布:伯努利是二项式的一个特例。

使用二项式的故事定义,让我们找到它的 PMF。

定理 $3.3 .5$(二项式 PMF)。如果 $X \sim \operatorname{Bin}(n, p)$,则 $X$ 的 PMF 为

$P(X=k)=\left(\begin{array}{l}n \ k\end{array}\right) p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}$

对于 $k=0,1, \ldots, n$(否则 $P(X=k)=0$)。

3.3.6。为了节省书写时间,PMF 在任何未指定为非零的地方通常都隐含为零,但无论如何重要的是要了解随机变量的支持是什么,以及检查 PMF 是否有效的良好做法.如果两个离散的 r.v.s 具有相同的 PMF,那么它们也必须具有相同的支撑。所以我们有时会提到离散分布的支持;这是任何房车的支持。与那个分布。

证明。由 $n$ 个独立伯努利试验组成的实验会产生一系列成功和失败。 $k$ 成功和 $n-k$ 失败的任何特定序列的概率是 $p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}$。有 $\left(\begin{array}{l}n \ k\end{array}\right)$ 这样的序列,因为我们只需要选择成功的地方。因此,设 $X$ 为成功次数,

$$

P(X=k)=\left(\begin{数组}{l}

n \

ķ

\end{数组}\right) p^{k}(1-p)^{n-k}

$$

对于 $k=0,1,\ldots,n$,否则 $P(X=k)=0$。这是一个有效的 PMF,因为它是

非负数,根据二项式定理求和为 1。

$$

P(X=k)=\le

R语言代写

统计代写|SAMPLE SPACES AND PEBBLE WORLD stat 代写 请认准UprivateTA™. UprivateTA™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。