博弈论代写代考| Ordinal Games 数学代写

博弈论代考

Une problem with the example about MIr. Holly s umbrella is that the payott points didn $t$ mean

anything. Is a payoff of 6 really worth twice what a payoff of 3 is worth? There are many games

where the payoffs are either subjective or difficult to measure numerically. In this section, we’ll

see that we can still retain something of the dynamics of the game if, instead of actual numerical

payoffs, all we know is in what order we prefer the outcomes of the game.

So assume there are two players, and we retain all the other assumptions (rational behavior, both

players have the same information about the payoffs, and the players move simultaneously and

independently). Suppose the row player has $m$ strategies, and the column player has $n$ strategies,

so that there are $r=m n$ outcomes in the game. Each player ranks the $r$ outcomes in order of his

or her preference. Mimicking what is done in Taylor and Pacelli (2008), we will assign the most

preferred outcome with the highest number $r$, because we are already accustomed to thinking that

a higher number is better for a player. Thus, the most preferred outcome is denoted $r$, the next most preferred is denoted $r-1$, etc., until the least preferred outcome, which is labeled 1. We

assume there are no two outcomes that the players prefer equally – no ties in the rankings. Then

we form ordered pairs of these preference rankings and use them to fill in the payoff matrix.

For example, suppose the row player has two strategies and the column player has three. The

payoff matrix might look like this:

$\left[\begin{array}{lll}(3,5) & (2,6) & (4,1) \ (6,2) & (1,4) & (5,3)\end{array}\right]$.

So, for example, in the $(1,1)$ position, the “payoff” $(3,5)$ indicates that this outcome is the

player’s second choice. The $(4,1)$ “payoff” indicates it is the row player’s third choice and the

column player’s last choice, etc. Because “first” (choice),

are ordizal mumbers, we call these games ordinal gand

First, we see what concepts from the usual theory carry over to ordinal games. Note that the

notions of “zero-sum” or “variable-sum” are meaningless. The “payoffs” are preference rankings

- so ordinal numbers – for which an addition is not even defined. However, some concepts carry

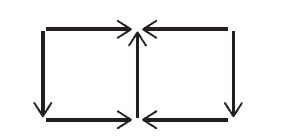

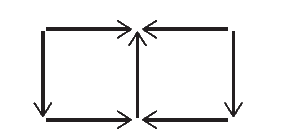

over just fine. The notion of a movement diagram, for example, still makes sense and is drawn

the same way as for variable-sum games. Vertical arrows point to the highest first coordinate in - Sensituity Amalysis, Ordinal Games, and n-Person Games

a column, and horizontal arrows point to the highe diagram for the matrix is shown in Figure $8.6$

diagram for the matrix is shown in Figure 8.6.

diagram for the matrix is shown in Figure 8.6.

The concept of one strategy dominating another also carries over.

DEFINITION 8.4 A strategy $S$ dominates a strategy $T$ if the player prefers every outcome in $S$

more than the corresponding outcome in $T$.

For the row player, that means every first coordinate of $S$ is higher than the corresponding first

coordinate in $T$; for the column player, every second coordinate in $S$ is higher than the corre-

sponding coordinate in $T$. In the preceding example, neither row dominates the other. However,

the middle column dominates both of the other two columns. As usual, you can read dominance in

the movement diagram since all the arrows point to the entries in the dominant row or column. (It’s

not obvious directly from the movement diagram, however, that neither the first column dominates

the third nor the reverse. One must look more closely at the payoff matrix.)

Similarly, the way to detect stability carries over as well.

DEFINITION $8.5$ An outcome of an ordinal game is called a Nash equilibrium if neither player

can improve the preference ranking of their payoff by a unilateral change of strategy.

As usual, Nash equilibria are evident from the movement diagram by virtue of being an outcome

to which both vertical and horizontal arrows point. In the preceding example, the outcome in the

1,2 position, with payoff $(2,6)$ is a Nash equilibrium.

The concept of a payoff polygon does not carry over because the payoffs are not real numbers.

Nevertheless, the concept of Pareto efficiency still makes sense:

DEFINITION $8.6$ An outcome of an ordinal game is Pareto efficient if there is no other outcome

that improves both players’ preferences.

374

Notice that in this definition it is not necessary to consider the case of just one player improving

because we have assumed there are no ties in the preference rankings for each player.

In the game just described, the Nash equilibrium is necessarily Pareto efficient because one of the players obtains his or her most preferred outcome 6 , so it is not possible to improve his or her

ranking.

8.2.2 Prisoners’ Dilemma and 0ther Dilemmas

Unfortunately, some of the difficulties we had with variable-sum games also carry over. There

are ordinal games where Nash equilibria are not Pareto efficient and games where they are not

Unfortunately, some of the difficulties we had with variable-sum games also carry over. There are ordinal games where Nash equilibria are not Pareto efficient and games where they are not

关于 MIr 的例子有一个问题。 Holly 的保护伞是,payott 积分没有 $t$ 意味着任何东西。 6 的收益真的是 3 的收益的两倍吗?有许多游戏

收益要么是主观的,要么难以用数字衡量。在本节中,我们将

看到我们仍然可以保留一些游戏的动态,如果我们所知道的不是实际的数字收益,而是我们更喜欢游戏结果的顺序。

br>所以假设有两个玩家,我们保留所有其他假设(理性行为,两个

玩家都有相同的收益信息,并且玩家同时

独立移动)。假设行玩家有 $m$ 策略,列玩家有 $n$ 策略,

因此游戏中有 $r=m n$ 个结果。每个玩家按其

偏好的顺序排列 $r$ 结果。模仿 Taylor 和 Paceli (2008) 中所做的,我们将分配具有最高数字 $r$ 的最

首选结果,因为我们已经习惯于认为

较高的数字对玩家更好。因此,最喜欢的结果表示为 $r$,其次最喜欢的结果表示为 $r-1$,依此类推,直到最不喜欢的结果被标记为 1。我们假设没有两个结果玩家同样喜欢 – 排名没有平局。然后

我们形成这些偏好排名的有序对,并使用它们来填充收益矩阵。

例如,假设行玩家有两种策略,而列玩家有三种策略。

收益矩阵可能如下所示:

$\left[\begin{array}{lll}(3,5) & (2,6) & (4,1) \ (6,2) & (1,4) & (5,3)\end{array}\right]$.

因此,例如,在 $(1,1)$ 位置,“收益”$(3,5)$ 表示这个结果是

玩家的第二选择。 $(4,1)$“payoff”表示它是行玩家的第三选择和

列玩家的最后选择,等等。因为“第一”(选择),

是序数,我们称这些游戏序数甘德

首先,我们看看通常理论中的哪些概念会延续到序数博弈中。请注意,“零和”或“变量和”的概念是没有意义的。 “收益”是偏好排名

- so 序数 – 甚至没有定义加法。但是,有些概念可以很好地继承

。例如,运动图的概念仍然有意义,并且绘制方式与可变和游戏相同。垂直箭头指向 - Sensituity Amalysis、Ordinal Games 和 n-Person Games

a 列中的最高第一个坐标,水平箭头指向矩阵的最高图,如图 $8.6$

矩阵图如图 8.6 所示。

矩阵图如图 8.6 所示。

一种策略支配另一种策略的概念也得以延续。

定义 8.4 策略 $S$如果玩家更喜欢 $S$ 中的每个结果

比 $T$ 中的相应结果更喜欢策略 $T$。

对于行玩家,这意味着 $S$ 的每个第一个坐标都高于$T$中对应的第一个

坐标;对于列播放器,$S$ 中的每一秒坐标都高于 $T$ 中相应的

对应坐标。在前面的示例中,两行都没有支配另一行。但是,

中间的列在其他两列中占主导地位。像往常一样,您可以在

运动图中阅读优势,因为所有箭头都指向优势行或列中的条目。 (但是,

从运动图中直接看不出来,第一列都不占优势

第三列也不是相反的。必须更仔细地查看收益矩阵。)

同样,检测方法稳定性也会延续。

定义 $8.5$ 如果没有参与者

不能通过单方面改变策略来提高其收益的偏好排名,则序数博弈的结果称为纳什均衡。

像往常一样,纳什均衡从运动图中显而易见,因为它是垂直和水平箭头所指向的结果

。在前面的示例中,

1,2 位置的结果,收益 $(2,6)$ 是纳什均衡。

收益多边形的概念不会延续,因为收益不是真实的

尽管如此,帕累托效率的概念仍然有意义:

定义 $8.6$ 如果没有其他结果可以改善两个玩家的偏好,则序数博弈的结果是帕累托有效的。

374

请注意,在此定义中,没有必要考虑只有一名玩家提高的情况

因为我们假设每个玩家的偏好排名没有关系。

在刚刚描述的游戏中,纳什均衡必然是帕累托有效的,因为其中一个参与者获得了他或她最喜欢的结果 6 ,

关于 MIr 的例子有一个问题。 Holly 的保护伞是,payott 积分没有 $t$ 意味着任何东西。 6 的收益真的是 3 的收益的两倍吗?有许多游戏

收益要么是主观的,要么难以用数字衡量。在本节中,我们将

看到我们仍然可以保留一些游戏的动态,如果我们所知道的不是实际的数字收益,而是我们更喜欢游戏结果的顺序。

br>所以假设有两个玩家,我们保留所有其他假设(理性行为,两个

玩家都有相同的收益信息,并且玩家同时

独立移动)。假设行玩家有 $m$ 策略,列玩家有 $n$ 策略,

因此游戏中有 $r=m n$ 个结果。每个玩家按其

偏好的顺序排列 $r$ 结果。模仿 Taylor 和 Paceli (2008) 中所做的,我们将分配具有最高数字 $r$ 的最

首选结果,因为我们已经习惯于认为

较高的数字对玩家更好。因此,最喜欢的结果表示为 $r$,其次最喜欢的结果表示为 $r-1$,依此类推,直到最不喜欢的结果被标记为 1。我们假设没有两个结果玩家同样喜欢 – 排名没有平局。然后

我们形成这些偏好排名的有序对,并使用它们来填充收益矩阵。

例如,假设行玩家有两种策略,而列玩家有三种策略。

收益矩阵可能如下所示:

$\left[\begin{array}{lll}(3,5) & (2,6) & (4,1) \ (6,2) & (1,4) & (5,3)\end{array}\right]$.

因此,例如,在 $(1,1)$ 位置,“收益”$(3,5)$ 表示这个结果是

玩家的第二选择。 $(4,1)$“payoff”表示它是行玩家的第三选择和

列玩家的最后选择,等等。因为“第一”(选择),

是序数,我们称这些游戏序数甘德

首先,我们看看通常理论中的哪些概念会延续到序数博弈中。请注意,“零和”或“变量和”的概念是没有意义的。 “收益”是偏好排名

博弈论代写

博弈论是关于什么的?当我妻子外出参加托斯卡纳的一个愉快的小型会议时,三位年轻女性邀请我与她们同桌共进午餐。当我坐下时,其中一个用闷热的声音说,“教我们如何玩爱情游戏”,但事实证明,他们想要的只是关于如何管理意大利男朋友的建议。我仍然认为他们拒绝我的战略建议是错误的,但他们正确地认为求爱是我们在现实生活中玩的许多不同类型的游戏之一在交通繁忙的司机正在玩驾驶游戏。在 eBay 上竞标的讨价还价者正在玩拍卖游戏。一家公司和一个工会正在谈判明年的工资,这是一场讨价还价的游戏。当反对的候选人在选举中选择他们的平台时,他们正在玩一场政治游戏。决定今天玉米片价格的杂货店老板正在玩一场经济游戏。简而言之,每当人类互动时,就会玩游戏。

每次新的巨额电信拍卖都需要根据将要运行的环境进行调整。不能像美国政府在聘请苏富比拍卖一堆卫星转发器时发现的那样,将设计从货架上拿下来。但也无法在数学模型中捕捉到新电信市场的所有复杂细节。因此,设计电信拍卖既是一门艺术,也是一门科学。一个人从简单的模型中推断出来,这些模型被选择来模仿似乎是问题的基本战略特征。

其他相关科目课程代写:组合学Combinatorics集合论Set Theory概率论Probability组合生物学Combinatorial Biology组合化学Combinatorial Chemistry组合数据分析Combinatorial Data Analysis

my-assignmentexpert愿做同学们坚强的后盾,助同学们顺利完成学业,同学们如果在学业上遇到任何问题,请联系my-assignmentexpert™,我们随时为您服务!

博弈论,又称为对策论(Game Theory)、赛局理论等,既是现代数学的一个新分支,也是运筹学的一个重要学科。 博弈论主要研究公式化了的激励结构间的相互作用,是研究具有斗争或竞争性质现象的数学理论和方法。 博弈论考虑游戏中的个体的预测行为和实际行为,并研究它们的优化策略。

计量经济学代考

计量经济学是以一定的经济理论和统计资料为基础,运用数学、统计学方法与电脑技术,以建立经济计量模型为主要手段,定量分析研究具有随机性特性的经济变量关系的一门经济学学科。 主要内容包括理论计量经济学和应用经济计量学。 理论经济计量学主要研究如何运用、改造和发展数理统计的方法,使之成为经济关系测定的特殊方法。

相对论代考

相对论(英語:Theory of relativity)是关于时空和引力的理论,主要由愛因斯坦创立,依其研究对象的不同可分为狭义相对论和广义相对论。 相对论和量子力学的提出给物理学带来了革命性的变化,它们共同奠定了现代物理学的基础。

编码理论代写

编码理论(英语:Coding theory)是研究编码的性质以及它们在具体应用中的性能的理论。编码用于数据压缩、加密、纠错,最近也用于网络编码中。不同学科(如信息论、电机工程学、数学、语言学以及计算机科学)都研究编码是为了设计出高效、可靠的数据传输方法。这通常需要去除冗余并校正(或检测)数据传输中的错误。

编码共分四类:[1]

数据压缩和前向错误更正可以一起考虑。

复分析代考

学习易分析也已经很冬年了,七七八人的也续了圧少的书籍和论文。略作总结工作,方便后来人学 Đ参考。

复分析是一门历史悠久的学科,主要是研究解析函数,亚纯函数在复球面的性质。下面一昭这 些基本内容。

(1) 提到复变函数 ,首先需要了解复数的基本性左和四则运算规则。怎么样计算复数的平方根, 极坐标与 $x y$ 坐标的转换,复数的模之类的。这些在高中的时候囸本上都会学过。

(2) 复变函数自然是在复平面上来研究问题,此时数学分析里面的求导数之尖的运算就会很自然的 引入到复平面里面,从而引出解析函数的定义。那/研究解析函数的性贡就是关楗所在。最关键的 地方就是所谓的Cauchy一Riemann公式,这个是判断一个函数是否是解析函数的关键所在。

(3) 明白解析函数的定义以及性质之后,就会把数学分析里面的曲线积分 $a$ 的概念引入复分析中, 定义几乎是一致的。在引入了闭曲线和曲线积分之后,就会有出现复分析中的重要的定理: Cauchy 积分公式。 这个是易分析的第一个重要定理。