博弈论代写代考| Equalizing Expectation 数学代写

博弈论代考

Since secrecy is important in a game that is not strictly determined, you normally would not expect to have any information about how your opponent will play when it is time to select your strategy. However, suppose you happen to know what mix your opponent is using, and you have reason to believe that he will continue to use that mix no matter what you do. Then how should you play?

We claim that instead of playing your optimal mix, you should respond by using a pure strategy.

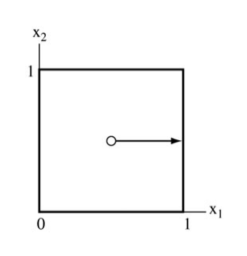

To see this, imagine you are the row player, and you know what mix $q$ the column player will use.

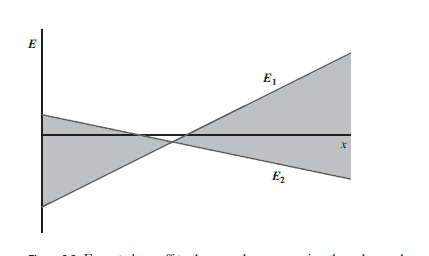

Use the formula $E_{i}=p_{i} A q$ to compute the expected payoff $E_{i}$ for each pure strategy $p_{i}$. If you were to use a mixed strategy $p$, your expected payoff $E=p A q$ would be a (weighted) average

were to use a mixed strategy $p$, your expected payoff $E=p A q$ would be a (weighted) average of the various $E_{i}$ values. But any weighted average of the numbers $E_{i}$ will always be between

the smallest $E_{i}$ and the largest. In particular, it will be less than the largest $E_{i}$, so you can obtain

a better expected payoff by simply using the pure strategy $p_{i}$ that produced the largest $E_{i}$ than

you could by using any mixed strategy. The argument works the same way if you are the column

player, except that you want $E$ to be small, not large, since the column player wants to minimize

the payoff to the row player. This proves a useful principle. Following Straffin (1993), we call it

the expected value principle.

THEOREM 6.27 The Expected Value Principle. Suppose you are playing a two-person constantsum game, and you know what mix your opponent is using, and you have reason to believe that she will continue to use that mix no matter what you do. The best response to this is to play that pure strategy that gives you the best expected payoff.

Before we illustrate this with examples, let’s be clear about which of our basic assumptions we are dropping. If you were to use a pure strategy in a constant-sum game with no saddle point and your opponent was rational and skillful, he would notice that you were using a pure strategy, and he would retaliate by changing his own strategy to take advantage of your play. So when we assume you have reason to believe that your opponent will not change his mix regardless of what you do, we are no longer assuming your opponent is rational or skillful. In most situations, your

hame Theory

opponent will be rational and skillful, so the expected value principle will not apply directly in these situations. However, we can imagine cases where it would apply (for example, in a game against nature or an indifferent opponent).

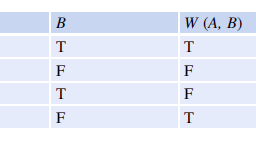

Now for some examples. Suppose that the payoff matrix is $2 \times 2$ with strategies we call $S$ and $T$ :

$$

A=\begin{gathered}

S \

T

\end{gathered}\left[\begin{array}{cc}

S & T \

3 & -1 \

-4 & 6

\end{array}\right]

$$

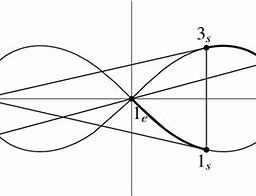

Suppose the column player will use $q=\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{array}\right]$ no matter what the ro hould the row player respond? Playing the first row $S$ means $p=p_{1}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}1 \ E_{1}=p_{1} A q=\left[\begin{array}{ll}1 & 0\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cc}3 & -1 \ -4 & 6\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{array}\right]=1.8 \text {. } \ \text { If we play the second row } T \text {, then } p=p_{2}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}0 & 1\end{array}\right] \text {, whence } \ E_{2}=p_{2} A q=\left[\begin{array}{cc}0 & 1\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cc}3 & -1 \ -4 & 6\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{array}\right]=-1 .\end{array}\right.$ Since $E_{1}=1.8$ is the better expected payoff for the row player, the expected iecommends playing row 1 , the pure strategy $S$. Actually, we can cut down involved. We made two computations, $p_{1} A q$ and $p_{2} A q$ where $p_{1}$ and $p_{2}$ ar can combine them into a single calculation by constructing a single matrix irst row and $p_{2}$ as its second row. Then, similar to examples we have seen in have promoted matrix multiplication as a good way to handle itemized comp matrix product $P A q$ will be a (column) matrix that contains both the $E_{i}$ values However, notice that $P=I$, the identity matrix! This means that $P A q=I$ words, the product $A q$ is a matrix whose entries are the $E_{i}$ values (which are to the row player for using the pure strategies $p_{i}$ ). We illustrate this in the example at hand: $$ \begin{array}{c}3 \ -4\end{array} \quad 6 \quad\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c}1.8 \ -1\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{l}E_{1} \ E_{2}\end{array}\right] . $$

Thus, this single computation achieves the same end as both of the individual computations. More generally, if $A$ has $m$ rows, the single matrix product $A q$ will replace $m$ distinct matrix products of three matrices each. A similar result holds if it is the row player whose mix $p$ is known and the column player is trying to use the expected value principle to determine the best entry (which is the best expected payoff for the column player). For example, if the row player decides to use the mix $p=\left[\begin{array}{cc}0.2 & 0.8\end{array}\right]$ and the column player knows this, then

$$

p A=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0.2 & 0.8

\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cc}

3 & -1 \

-4 & 6

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

-2.6 & 4.6

\end{array}\right] .

$$

Since $-2.6$ represents the better payoff for the column player, the expected value principle recommends that the first column $S$ should be played. Summarizing, we have the following corollary.

由于保密在没有严格确定的游戏中很重要,因此您通常不会期望在选择策略时获得有关对手将如何玩的任何信息。但是,假设您碰巧知道对手使用的是什么组合,并且您有理由相信无论您做什么,他都会继续使用该组合。那你应该怎么玩?

我们声称,您应该使用纯粹的策略来应对,而不是发挥您的最佳组合。

要看到这一点,假设您是行播放器,并且您知道列播放器将使用什么混合 $q$。

使用公式 $E_{i}=p_{i} A q$ 计算每个纯策略 $p_{i}$ 的预期收益 $E_{i}$。如果您使用混合策略 $p$,您的预期收益 $E=p A q$ 将是(加权)平均值

如果使用混合策略 $p$,您的预期收益 $E=p A q$ 将是各种 $E_{i}$ 值的(加权)平均值。但是任何数字 $E_{i}$ 的加权平均值总是介于

最小的 $E_{i}$ 和最大的。特别是它会小于最大的$E_{i}$,所以可以得到

通过简单地使用产生最大 $E_{i}$ 的纯策略 $p_{i}$ 来获得更好的预期收益

您可以使用任何混合策略。如果您是列,则该参数的工作方式相同

播放器,除了您希望 $E$ 小而不是大,因为列播放器想要最小化

行玩家的回报。这证明了一个有用的原则。根据 Straffin (1993),我们称之为

期望值原则。

定理 6.27 期望值原理。假设你正在玩一个两人常数和游戏,并且你知道你的对手正在使用什么组合,并且你有理由相信无论你做什么,她都会继续使用这种组合。对此的最佳回应是采用能够为您提供最佳预期回报的纯粹策略。

在我们用例子说明这一点之前,让我们弄清楚我们放弃了哪些基本假设。如果你在无鞍点的恒和博弈中使用纯策略,而你的对手是理性且熟练的,他会注意到你使用的是纯策略,他会通过改变自己的策略来报复你的戏。所以当我们假设你有理由相信你的对手无论你做什么都不会改变他的组合,我们不再假设你的对手是理性的或熟练的。在大多数情况下,您的

火腿理论

对手将是理性和熟练的,因此期望值原则不会直接适用于这些情况。但是,我们可以想象它适用的情况(例如,在与自然或冷漠的对手的游戏中)。

现在举一些例子。假设收益矩阵是 $2 \times 2$,我们称之为 $S$ 和 $T$ 的策略:

$$

A=\开始{聚集}

S \

吨

\end{聚集}\left[\begin{array}{cc}

英石 \

3 & -1 \

-4 & 6

\end{数组}\right]

$$

假设列播放器将使用 $q=\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{array}\right]$ ,无论行播放器应该响应什么?播放第一行 $S$ 意味着 $p=p_{1}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}1 \ E_{1}=p_{1} A q=\left[\begin{array} {ll}1 & 0\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cc}3 & -1 \ -4 & 6\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array }{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{数组}\right]=1.8 \text {。 } \ \text { 如果我们播放第二行 } T \text {,则 } p=p_{2}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}0 & 1\end{array}\right] \ text {, wherece } \ E_{2}=p_{2} A q=\left[\begin{array}{cc}0 & 1\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ cc}3 & -1 \ -4 & 6\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\end{array}\right]=-1 .\end{ array}\right.$ 由于 $E_{1}=1.8$ 是行玩家的更好预期收益,因此预期 iecommends 玩第 1 行,纯策略 $S$。实际上,我们可以减少参与。我们进行了两次计算,$p_{1} A q$ 和 $p_{2} A q$ 其中 $p_{1}$ 和 $p_{2}$ ar 可以通过首先构造单个矩阵将它们组合成单个计算行和 $p_{2}$ 作为第二行。然后,与我们看到的示例类似,将矩阵乘法提升为处理逐项比较矩阵乘积的好方法 $PA q$ 将是一个包含两个 $E_{i}$ 值的(列)矩阵但是,请注意 $ P=I$,单位矩阵!这意味着 $PA q=I$ 单词,产品 $A q$ 是一个矩阵,其条目是 $E_{i}$ 值(对于使用纯策略 $p_{i}$ 的行玩家) .我们在手头的例子中说明了这一点: $$ \begin{array}{c}3 \ -4\end{array} \quad 6 \quad\left[\begin{array}{c}0.7 \ 0.3\ end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{c}1.8 \ -1\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{l}E_{1} \ E_{2}\end{array}\right] 。 $$

因此,这个单一的计算实现了与两个单独的计算相同的目的。更一般地,如果 $A$ 有 $m$ 行,则单个矩阵乘积 $A q$ 将替换 $m$ 不同的矩阵乘积,每个矩阵乘积三个矩阵。如果行播放器的混合 $p$ 已知并且列播放器是 tryi,则类似的结果成立

博弈论代写

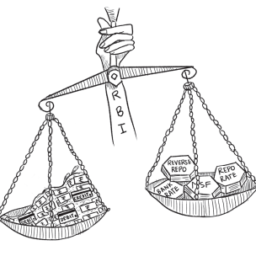

博弈论是关于什么的?当我妻子外出参加托斯卡纳的一个愉快的小型会议时,三位年轻女性邀请我与她们同桌共进午餐。当我坐下时,其中一个用闷热的声音说,“教我们如何玩爱情游戏”,但事实证明,他们想要的只是关于如何管理意大利男朋友的建议。我仍然认为他们拒绝我的战略建议是错误的,但他们正确地认为求爱是我们在现实生活中玩的许多不同类型的游戏之一在交通繁忙的司机正在玩驾驶游戏。在 eBay 上竞标的讨价还价者正在玩拍卖游戏。一家公司和一个工会正在谈判明年的工资,这是一场讨价还价的游戏。当反对的候选人在选举中选择他们的平台时,他们正在玩一场政治游戏。决定今天玉米片价格的杂货店老板正在玩一场经济游戏。简而言之,每当人类互动时,就会玩游戏。

每次新的巨额电信拍卖都需要根据将要运行的环境进行调整。不能像美国政府在聘请苏富比拍卖一堆卫星转发器时发现的那样,将设计从货架上拿下来。但也无法在数学模型中捕捉到新电信市场的所有复杂细节。因此,设计电信拍卖既是一门艺术,也是一门科学。一个人从简单的模型中推断出来,这些模型被选择来模仿似乎是问题的基本战略特征。

其他相关科目课程代写:组合学Combinatorics集合论Set Theory概率论Probability组合生物学Combinatorial Biology组合化学Combinatorial Chemistry组合数据分析Combinatorial Data Analysis

my-assignmentexpert愿做同学们坚强的后盾,助同学们顺利完成学业,同学们如果在学业上遇到任何问题,请联系my-assignmentexpert™,我们随时为您服务!

博弈论,又称为对策论(Game Theory)、赛局理论等,既是现代数学的一个新分支,也是运筹学的一个重要学科。 博弈论主要研究公式化了的激励结构间的相互作用,是研究具有斗争或竞争性质现象的数学理论和方法。 博弈论考虑游戏中的个体的预测行为和实际行为,并研究它们的优化策略。

计量经济学代考

计量经济学是以一定的经济理论和统计资料为基础,运用数学、统计学方法与电脑技术,以建立经济计量模型为主要手段,定量分析研究具有随机性特性的经济变量关系的一门经济学学科。 主要内容包括理论计量经济学和应用经济计量学。 理论经济计量学主要研究如何运用、改造和发展数理统计的方法,使之成为经济关系测定的特殊方法。

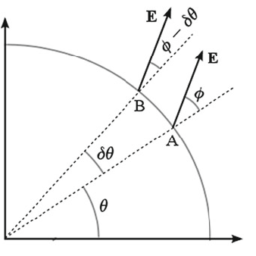

相对论代考

相对论(英語:Theory of relativity)是关于时空和引力的理论,主要由愛因斯坦创立,依其研究对象的不同可分为狭义相对论和广义相对论。 相对论和量子力学的提出给物理学带来了革命性的变化,它们共同奠定了现代物理学的基础。

编码理论代写

编码理论(英语:Coding theory)是研究编码的性质以及它们在具体应用中的性能的理论。编码用于数据压缩、加密、纠错,最近也用于网络编码中。不同学科(如信息论、电机工程学、数学、语言学以及计算机科学)都研究编码是为了设计出高效、可靠的数据传输方法。这通常需要去除冗余并校正(或检测)数据传输中的错误。

编码共分四类:[1]

数据压缩和前向错误更正可以一起考虑。

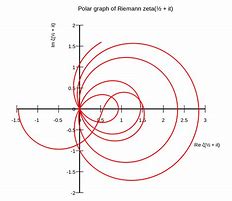

复分析代考

学习易分析也已经很冬年了,七七八人的也续了圧少的书籍和论文。略作总结工作,方便后来人学 Đ参考。

复分析是一门历史悠久的学科,主要是研究解析函数,亚纯函数在复球面的性质。下面一昭这 些基本内容。

(1) 提到复变函数 ,首先需要了解复数的基本性左和四则运算规则。怎么样计算复数的平方根, 极坐标与 $x y$ 坐标的转换,复数的模之类的。这些在高中的时候囸本上都会学过。

(2) 复变函数自然是在复平面上来研究问题,此时数学分析里面的求导数之尖的运算就会很自然的 引入到复平面里面,从而引出解析函数的定义。那/研究解析函数的性贡就是关楗所在。最关键的 地方就是所谓的Cauchy一Riemann公式,这个是判断一个函数是否是解析函数的关键所在。

(3) 明白解析函数的定义以及性质之后,就会把数学分析里面的曲线积分 $a$ 的概念引入复分析中, 定义几乎是一致的。在引入了闭曲线和曲线积分之后,就会有出现复分析中的重要的定理: Cauchy 积分公式。 这个是易分析的第一个重要定理。