数学代写| Generalizations 数论代考

数论代考

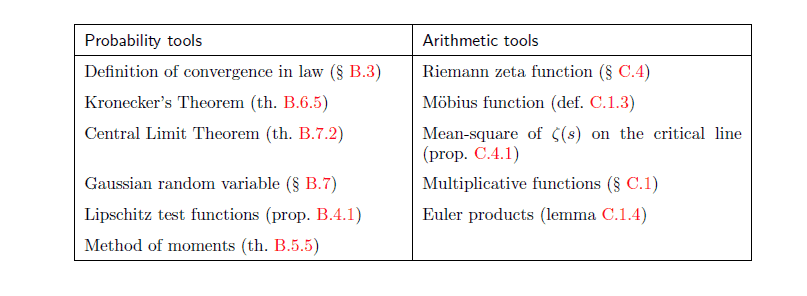

If we look pack at the proof of Bagchi’s Theorem, and at the proof of Voronin’s Theorem, we can see precisely which arithmetic ingredients appeared. They are the following:

- The crucial link between the arithmetic objects and the probabilistic model is provided by Proposition $3.2 .5$, which depends on the unique factorization of integers into primes; this is an illustration of the asymptotic independence of prime numbers, similarly to Proposition 1.3.7;

- The proof of Bagchi’s theorem then relies on the mean-value property (3.11) of the Riemann zeta function; this estimate has arithmetic meaning;

- The Prime Number Theorem, which appears in the proof of Voronin’s Theorem, in order to control the distribution of primes in (roughly) dyadic intervals.

Note that some arithmetic features remain in the Random Dirichlet Series that arises as the limit in Bagchi’s Theorem, in contrast with the Erdős-Kac Theorem, where the limit is the universal gaussian distribution. This means, in particular, that going beyond Bagchi’s Theorem to applications (as in Voronin’s Theorem) still naturally involves arithmetic problems, many of which are very interesting in their interaction with probability theory (see below for a few references).

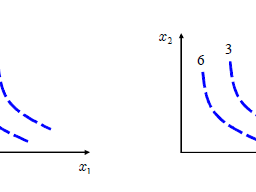

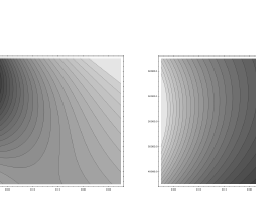

From this analysis, it shouldn’t be very surprising that Bagchi’s Theorem can be generalized to many other situations. The most interesting concerns perhaps the limiting behavior, in $\mathrm{H}(\mathrm{D})$, of families of L-functions of the type

$$

\mathrm{L}(f, s)=\sum_{n \geqslant 1} \lambda_{f}(n) n^{-s}

$$

where $f$ runs over some sequence of arithmetic objects with associated L-functions, ordered in a sequence of probability spaces (which need not be continuous like $\Omega_{\mathrm{T}}$ ). We refer to [59, Ch. 5] for a survey and discussion of L-functions, and to [69] for a discussion of families of L-functions. There are some rather elementary special cases, such as the vertical translates $\mathrm{L}(\chi, s+i t)$ of a fixed Dirichlet $\mathrm{L}$-function $\mathrm{L}(\chi, s)$, since almost all properties of the Riemann zeta function extend quite easily to this case. Another interesting case is the finite set $\Omega_{q}$ of non-trivial Dirichlet characters modulo a prime number $q$, with the uniform probability measure. Then one can look at the distribution can check that Bagchi’s Theorem extends to this situation.

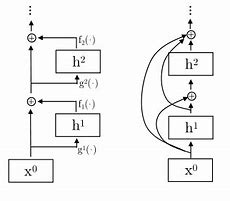

A second example, which is treated in [72] is, still for a prime $q \geqslant 2$, the set $\Omega_{q}$ of holomorphic cuspidal modular forms of weight 2 and level $q$, either with the uniform probability measure, or with that provided by the Petersson formula $([69,31$, ex. 8]). An analogue of Bagchi’s Theorem holds, but the limiting random Dirichlet series is not the same as in Theorem 3.2.1: with the Petersson average, it is

$$

\prod_{p}\left(1-\mathrm{X}{p} p^{-s}+p^{-2 s}\right)^{-1} $$ where $\left(\mathrm{X}{p}\right)$ is a sequence of independent random variables, which are all distributed according to the Sato-Tate measure (the same that appears in Example B.6.1 (3)). This different limit is simply due to the form that “local spectral equidistribution” (in the sense of $[69]$ ) takes for this family $($ see $[69,38])$. Indeed, the local spectral equidistribution

57

property plays the role of Proposition 3.2.5. The analogue of (3.11) follows from a stronger mean-square formula, using the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality: there exists a constant A $>0$ such that, for any $\sigma_{0}>1 / 2$ and all $s \in C$ with $\operatorname{Re}(s) \geqslant \sigma_{0}$, we have

$$

\sum_{f \in \Omega_{q}} \omega_{f}|\mathrm{~L}(f, s)|^{2} \ll(1+|s|)^{\mathrm{A}}

$$

for $q \geqslant 2$, where $\omega_{f}$ is the Petersson-averaging weight (see [76, Prop. 5], which proves an even more difficult result where $\operatorname{Re}(s)$ can be as small as $\left.\frac{1}{2}+c(\log q)^{-1}\right)$.

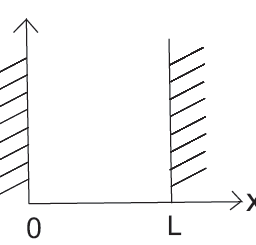

However, extending Bagchi’s Theorem to many other families of L-functions (e.g., vertical translates of an L-function of higher rank) requires restrictions, in the current state of knowledge. The reason is that the analogue of the mean-value estimates (3.11) or $(3.15)$ is usually only known when $\operatorname{Re}(s) \geqslant \sigma_{0}>1 / 2$, for some $\sigma_{0}$ such that $\sigma_{0}<1$. Then the only domains D for which one can prove a version of Bagchi’s Theorem are those contained in $\operatorname{Re}(s)>\sigma_{0}$.

[Further references: Titchmarsh [117], especially Chapter 11, discusses the older work of Bohr and Jessen, which has some interesting geometric aspects that are not apparent in modern treatments. Bagchi’s Thesis [4] contains some generalizations as well as more information concerning the limit theorem and Voronin’s Theorem…]

如果我们看一下 Bagchi 定理的证明和 Voronin 定理的证明,我们可以准确地看到出现了哪些算术成分。它们是:

- 算术对象和概率模型之间的关键联系由命题 $3.2 .5$ 提供,它依赖于整数到素数的唯一分解;这是质数渐近独立性的说明,类似于命题 1.3.7;

- Bagchi 定理的证明依赖于黎曼 zeta 函数的均值性质 (3.11);这个估计有算术意义;

- 出现在沃罗宁定理证明中的素数定理,用于控制(大致)二元区间中素数的分布。

请注意,与 Erdős-Kac 定理相比,随机 Dirichlet 级数中保留了一些算术特征,这些特征是 Bagchi 定理中的极限,极限是通用高斯分布。这尤其意味着,超越 Bagchi 定理到应用程序(如在 Voronin 定理中)仍然自然涉及算术问题,其中许多在与概率论的相互作用中非常有趣(参见下面的一些参考资料)。

从这个分析来看,Bagchi 定理可以推广到许多其他情况也就不足为奇了。最有趣的可能是在 $\mathrm{H}(\mathrm{D})$ 中,类型的 L-函数族的限制行为

$$

\mathrm{L}(f, s)=\sum_{n \geqslant 1} \lambda_{f}(n) n^{-s}

$$

其中 $f$ 运行在具有相关 L 函数的一些算术对象序列上,按概率空间序列排序(不必像 $\Omega_{\mathrm{T}}$ 那样是连续的)。我们参考 [59, Ch. 5] 用于 L 函数的调查和讨论,以及 [69] 用于 L 函数族的讨论。有一些相当基本的特殊情况,例如垂直平移 $\mathrm{L}(\chi, s+it)$ 的固定 Dirichlet $\mathrm{L}$-函数 $\mathrm{L}(\chi , s)$,因为几乎所有黎曼 zeta 函数的性质都可以很容易地扩展到这种情况。另一个有趣的例子是非平凡狄利克雷字符的有限集 $\Omega_{q}$ 以一个素数 $q$ 为模,具有统一的概率测度。然后可以查看分布可以检查 Bagchi 定理是否扩展到这种情况。

在 [72] 中处理的第二个例子仍然是对于素数 $q \geqslant 2$,权重为 2 和水平 $q$ 的全纯尖瓣模形式的集合 $\Omega_{q}$,或者具有统一概率测度,或使用 Petersson 公式 $([69,31$, ex. 8]) 提供的测度。 Bagchi 定理的类似物成立,但限制随机 Dirichlet 级数与定理 3.2.1 中的不同:使用 Petersson 平均值,它是

$$

\prod_{p}\left(1-\mathrm{X}{p} p^{-s}+p^{-2 s}\right)^{-1} $$ 其中 $\left(\mathrm{X}{p}\right)$ 是一系列独立随机变量,这些变量均按照 Sato-Tate 测度分布(与示例 B.6.1 (3) 中出现的相同) )。这种不同的限制仅仅是由于“局部光谱均匀分布”(在 $[69]$ 的意义上)对这个家庭 $($ 参见 $[69,38])$ 采取的形式。实际上,局部光谱均匀分布

57

财产扮演命题 3.2.5 的角色。 (3.11) 的类似物来自一个更强的均方公式,使用 Cauchy-Schwarz 不等式:存在一个常数 A $>0$ 使得对于任何 $\sigma_{0}>1 / 2$ 和所有 $ s \in C$ 和 $\operatorname{Re}(s) \geqslant \sigma_{0}$,我们有

$$

\sum_{f \in \Omega_{q}} \omega_{f}|\mathrm{~L}(f, s)|^{2} \ll(1+|s|)^{\mathrm{A} }

$$

对于 $q \geqslant 2$,其中 $\omega_{f}$ 是 Petersson 平均权重(参见 [76, Prop. 5],这证明了一个更加困难的结果,其中 $\operatorname{Re}(s)$可以小到 $\left.\frac{1}{2}+c(\log q)^{-1}\right)$。

然而,在当前的知识状态下,将 Bagchi 定理扩展到许多其他 L 函数族(例如,更高级别的 L 函数的垂直转换)需要限制。原因是平均值估计值 (3.11) 或 $(3.15)$ 的类比通常仅在 $\operatorname{Re}(s) \geqslant \sigma_{0}>1 / 2$ 时才知道,对于某些$\sigma_{0}$ 使得 $\sigma_{0}<1$。那么,唯一可以证明 Bagchi 定理版本的域 D 是那些包含在 $\operatorname{Re}(s)>\sigma_{0}$ 中的域。

[更多参考资料:Titchmarsh [117],特别是第 11 章,讨论了 Bohr 和 Jessen 的较早作品,其中有一些在现代治疗中不明显的有趣的几何方面。 Bagchi 的论文 [4] 包含一些概括以及有关极限定理和 Voronin 定理的更多信息…]

数论代写

数论是纯粹数学的分支之一,主要研究整数的性质。整数可以是方程式的解(丢番图方程)。有些解析函数(像黎曼ζ函数)中包括了一些整数、质数的性质,透过这些函数也可以了解一些数论的问题。透过数论也可以建立实数和有理数之间的关系,并且用有理数来逼近实数(丢番图逼近)。

按研究方法来看,数论大致可分为初等数论和高等数论。初等数论是用初等方法研究的数论,它的研究方法本质上说,就是利用整数环的整除性质,主要包括整除理论、同余理论、连分数理论。高等数论则包括了更为深刻的数学研究工具。它大致包括代数数论、解析数论、计算数论等等。

其他相关科目课程代写:组合学Combinatorics集合论Set Theory概率论Probability组合生物学Combinatorial Biology组合化学Combinatorial Chemistry组合数据分析Combinatorial Data Analysis

my-assignmentexpert愿做同学们坚强的后盾,助同学们顺利完成学业,同学们如果在学业上遇到任何问题,请联系my-assignmentexpert™,我们随时为您服务!

在中世纪时,除了1175年至1200年住在北非和君士坦丁堡的斐波那契有关等差数列的研究外,西欧在数论上没有什么进展。

数论中期主要指15-16世纪到19世纪,是由费马、梅森、欧拉、高斯、勒让德、黎曼、希尔伯特等人发展的。最早的发展是在文艺复兴的末期,对于古希腊著作的重新研究。主要的成因是因为丢番图的《算术》(Arithmetica)一书的校正及翻译为拉丁文,早在1575年Xylander曾试图翻译,但不成功,后来才由Bachet在1621年翻译完成。

计量经济学代考

计量经济学是以一定的经济理论和统计资料为基础,运用数学、统计学方法与电脑技术,以建立经济计量模型为主要手段,定量分析研究具有随机性特性的经济变量关系的一门经济学学科。 主要内容包括理论计量经济学和应用经济计量学。 理论经济计量学主要研究如何运用、改造和发展数理统计的方法,使之成为经济关系测定的特殊方法。

相对论代考

相对论(英語:Theory of relativity)是关于时空和引力的理论,主要由愛因斯坦创立,依其研究对象的不同可分为狭义相对论和广义相对论。 相对论和量子力学的提出给物理学带来了革命性的变化,它们共同奠定了现代物理学的基础。

编码理论代写

编码理论(英语:Coding theory)是研究编码的性质以及它们在具体应用中的性能的理论。编码用于数据压缩、加密、纠错,最近也用于网络编码中。不同学科(如信息论、电机工程学、数学、语言学以及计算机科学)都研究编码是为了设计出高效、可靠的数据传输方法。这通常需要去除冗余并校正(或检测)数据传输中的错误。

编码共分四类:[1]

数据压缩和前向错误更正可以一起考虑。

复分析代考

学习易分析也已经很冬年了,七七八人的也续了圧少的书籍和论文。略作总结工作,方便后来人学 Đ参考。

复分析是一门历史悠久的学科,主要是研究解析函数,亚纯函数在复球面的性质。下面一昭这 些基本内容。

(1) 提到复变函数 ,首先需要了解复数的基本性左和四则运算规则。怎么样计算复数的平方根, 极坐标与 $x y$ 坐标的转换,复数的模之类的。这些在高中的时候囸本上都会学过。

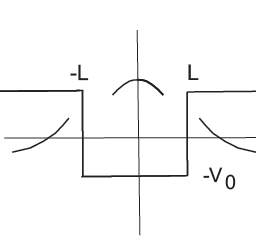

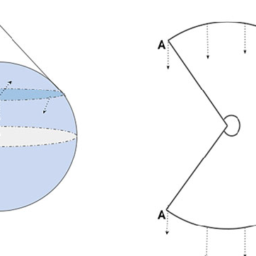

(2) 复变函数自然是在复平面上来研究问题,此时数学分析里面的求导数之尖的运算就会很自然的 引入到复平面里面,从而引出解析函数的定义。那/研究解析函数的性贡就是关楗所在。最关键的 地方就是所谓的Cauchy一Riemann公式,这个是判断一个函数是否是解析函数的关键所在。

(3) 明白解析函数的定义以及性质之后,就会把数学分析里面的曲线积分 $a$ 的概念引入复分析中, 定义几乎是一致的。在引入了闭曲线和曲线积分之后,就会有出现复分析中的重要的定理: Cauchy 积分公式。 这个是易分析的第一个重要定理。