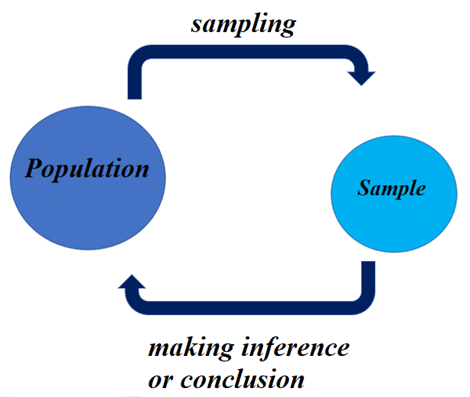

如果你也在 怎样代写统计推断Statistical Inference 这个学科遇到相关的难题,请随时右上角联系我们的24/7代写客服。统计推断Statistical Inference是利用数据分析来推断概率基础分布的属性的过程。推断性统计分析推断人口的属性,例如通过测试假设和得出估计值。假设观察到的数据集是从一个更大的群体中抽出的。

统计推断Statistical Inference(可以与描述性统计进行对比。描述性统计只关注观察到的数据的属性,它并不依赖于数据来自一个更大的群体的假设。在机器学习中,推理一词有时被用来代替 “通过评估一个已经训练好的模型来进行预测”;在这种情况下,推断模型的属性被称为训练或学习(而不是推理),而使用模型进行预测被称为推理(而不是预测);另见预测推理。

统计推断Statistical Inference代写,免费提交作业要求, 满意后付款,成绩80\%以下全额退款,安全省心无顾虑。专业硕 博写手团队,所有订单可靠准时,保证 100% 原创。最高质量的统计推断Statistical Inference作业代写,服务覆盖北美、欧洲、澳洲等 国家。 在代写价格方面,考虑到同学们的经济条件,在保障代写质量的前提下,我们为客户提供最合理的价格。 由于作业种类很多,同时其中的大部分作业在字数上都没有具体要求,因此统计推断Statistical Inference作业代写的价格不固定。通常在专家查看完作业要求之后会给出报价。作业难度和截止日期对价格也有很大的影响。

同学们在留学期间,都对各式各样的作业考试很是头疼,如果你无从下手,不如考虑my-assignmentexpert™!

my-assignmentexpert™提供最专业的一站式服务:Essay代写,Dissertation代写,Assignment代写,Paper代写,Proposal代写,Proposal代写,Literature Review代写,Online Course,Exam代考等等。my-assignmentexpert™专注为留学生提供Essay代写服务,拥有各个专业的博硕教师团队帮您代写,免费修改及辅导,保证成果完成的效率和质量。同时有多家检测平台帐号,包括Turnitin高级账户,检测论文不会留痕,写好后检测修改,放心可靠,经得起任何考验!

统计代写|统计推断代考Statistical Inference代写|The Paradox of Precision

The next two problems result from asymmetries between the null and alternative hypotheses.

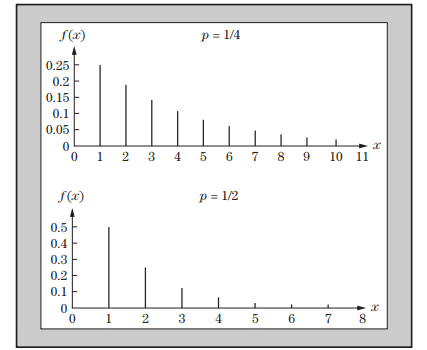

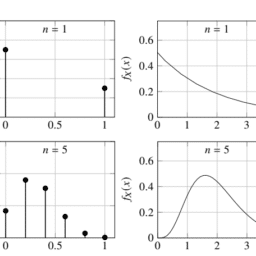

The first is the problem of testing a point null against a diffuse alternative. So long as the null represents only a zero (or some other) point, any other point, no matter how close, counts as an alternative. Suppose we are trying to determine whether a given coin is biased; the probability with which it yields a head will be some value in the continuous range from 0 to 1 , of which the hypothesized value, .5 , represents but an infinitesimal point. If there is any bias, however slight, it will show up as significant in a sufficiently large number of trials. Thus we arrive at an insight into Bernoulli’s Theorem which is opposite to the usual intuition:

If the chance of an event occurring in a single trial is estimated to be $p^{\prime}$, then the probability that the ratio of the number of times the event occurs to the number of trials differs from $p$, by an amount of any significance, however great, can be made as near certainty as desired by increasing the number of trials. Spencer Brown, 1957, p. 90; original in italics

We might call this the perverse form of Bernoulli’s Theorem.

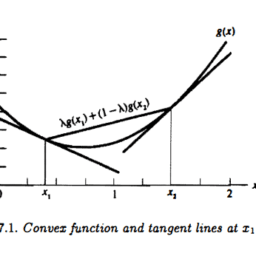

Now, Bakan (1966) and others have pointed out that there are few, if any, exact true nulls in nature. Consequently, we can virtually be assured of significance, whatever hypothesis we test, with a large enough sample. The prospect of “too large” a sample has led some writers (e.g., Binder, 1963; Hays, 1963) to recommend that investigators specify a size of effect they were interested in detecting, prior to doing the experiment. If we are prepared to say with what probability we should like to pick up effects of a given size, then the requisite sample size can be calculated. Research psychologists have generally been reluctant to adopt this solution, however, because it entails a nakedly personal judgment about how big a difference must be to matter. There are not, and could not be, any uniform, objective criteria for what size effect is theoretically interesting or important. In fact, it is largely to avoid this particular judgment that psychologists have relied so universally on significance tests, to answer questions which arguably are about substantive significance. Research practice changed in the late twentieth century, when the federal government began requiring power analysis for grants. Psychologists were saved from exercising judgment by Cohen’s (1962, 1977) classification of effect sizes, though he himself cautioned that an effect size that would be considered small in some contexts might be considered medium in others.

统计代写|统计推断代考Statistical Inference代写|Identifcation with the Null

In the usual practice of Fisherian significance testing, the theoretical hypothesis, the one that is actually believed, is represented by the diffuse alternative, and the point null represents the denial of any such effect. Thus significant results count in favor of the hypothesis, and we have a rejection-support (r-s) scheme, to use Binder’s (1963) terminology. Occasionally situations arise, however, where it is logical to identify the theory with the null; the theory itself makes the claim of no effect. A common example of such an acceptance-support (a-s) scheme is the matching of two groups on background variables; we want to be able to assert that they do not differ.

The problem is most acute in Fisherian theory, which does not sanction acceptance of the null hypothesis (“proving the nonexistence of a difference”). Neyman-Pearson theory, which does not single out one hypothesis as the null, is slightly better off in this respect. Neyman (1942) contends that it is in principle arbitrary which hypothesis is designated as the null; since, however, the theory still treats errors asymmetrically, he suggests identifying the hypothesis tested as the one for which false rejections would be more costly. In psychological research the concept of costs of false rejections is a little vague, but it has generally been agreed, in the interest of scientific conservatism, that it is worse to declare the existence of an effect when there is none than to fail to discover a true difference. This resolution, at any rate, enabled Neyman-Pearson theory to be mapped onto Fisherian practice. The freedom, within Neyman-Pearson theory, to test either hypothesis or its denial is very seldom exercised, for the reason that it pertains only to point alternatives. A sampling distribution cannot be derived from a diffuse lumpen-hypothesis.

The result has been that our only accredited means of denying a difference has been to assert that the difference failed to reach significance. The procedure is awkward and unsatisfying, first because it is only the negation of a negation of a negation (failure to find evidence against the assertion of no difference), and second because it appears rather strongly biased in favor of the tester, with $95 \%$ (or 99\%) of the distribution of outcomes counting for the null. Logically, it would be possible to designate a narrow band $(5 \%, 10 \%, 20 \%)$ around the null point and assert the null only if the outcome fell in this center portion of the distribution, but the practice has never caught on. It would be an effective lesson, however, regarding the variability of small samples.

统计推断代写

统计代写|统计推断代考STATISTICAL INFERENCE代 写|THE PARADOX OF PRECISION

接下来的两个问题是由原假设和备择假设之间的不对称引起的。

第一个是针对扩散替代测试零点的问题。只要 null 只代表零orsomeother点,任何其他点,无论多么接近,都算作备选方案。假设 我们正在尝试确定给定的硬币是否有偏差;它产生正面的概率将是从 0 到 1 的连续范围内的某个值,其中假设值 .5 只代表一个无穷 小的点。如果存在任何偏差,无论多么轻微,它都会在足够多的试验中显示为显着。因此,我们对伯努利定理有了深刻的认识,这 与通常的直觉相反:

如果一个事件在单次试验中发生的概率估计为 $p^{\prime}$ ,则事件发生次数与试验次数之比不同于 $p$, 任何显着性的数量,无论多么重要,都 可以通过增加试验次数来达到所需的接近确定性。斯宾塞·布朗 (Spencer Brown),1957 年,p. 90;原文为斜体 我们可以称其为伯努利定理的反常形式。

现在,巴坎1966和其他人指出,自然界中几乎没有(如果有的话)完全正确的零。因此,无论我们用足够大的样本检验什么假设, 我们几乎都可以确信其显着性。样本“太大”的前景导致一些作者e. g., Binder, $1963 ;$ Hays, 1963 建议研究人员在进行实验之前指定 他们有兴趣检测的效果大小。如果我们准备好说出我们希望以多大的概率获得给定大小的影响,则可以计算出所需的样本大小。然 而,研究心理学家通常不愿意采用这种解决方案,因为它需要赤裸裸的个人判断,即差异必须有多大才重要。对于理论上有趣或重 要的大小效应,没有也不可能有任何统一的客观标准。事实上,很大程度上是为了避免这种特殊的判断,心理学家如此普遍地依赖 重要性测试来回答可以说是关于实质意义的问题。研究实践在二十世纪后期发生了变化,当联邦政府开始要求对拨款进行权力分析 时。科恩的理论使心理学家免于做出判断 1962,1977 效应量的分类,尽管他自己警告说,在某些情况下被认为很小的效应量在其他 情况下可能被认为是中等。

统计代写|统计推断代考STATISTICAL INFERENCE代 写|IDENTIFCATION WITH THE NULL

在Fisherian 显着性检验的通常实践中,理论假设,即实际相信的假设,由扩散备选方案表示,零点表示拒绝任何此类影响。因此, 逻辑的情况;

这个问题在Fisherian 理论中最为少锐,它不认可零假没的接受 “provingthenonexistenceofadifference”. Neyman-Pearson理论 不挑出一个假设作为零假设,在这方面梢好一些。内曼 1942 主张将㑚个假设指定为无效原则原则上是任意的;然而,由于该理论

何,这一决议使内曼皮尔逊理论能昜映㧶到费希尔实践中。在内曼皮尔逊理论中,很少行使泣验叚设或否定假没的自由,因为它只 适用于点选择。

结果是,我们唯一认可的否认差异的方法是断言差异没有达到显着性。这个过程是榄於和不令人满意的,首先是因为它只是一个否 定的否定的否定 failuretofindevidenceagainsttheassertionofnodifference,其次是因为它似平非常偏向于测试者, $95 \%$ or $99 \%$ 结果的分布计算为零。从逻偮上讲,可以指定一个穴带 $(5 \%, 10 \%, 20 \%)$ 围绕零点并仅当结果落在分布的这个中心部分时才断 言零,但这种做法从末流行过。然而,关于小样本的可变性,文将是一个有效的教训

统计代写|统计推断代考Statistical Inference代写 请认准exambang™. exambang™为您的留学生涯保驾护航。

微观经济学代写

微观经济学是主流经济学的一个分支,研究个人和企业在做出有关稀缺资源分配的决策时的行为以及这些个人和企业之间的相互作用。my-assignmentexpert™ 为您的留学生涯保驾护航 在数学Mathematics作业代写方面已经树立了自己的口碑, 保证靠谱, 高质且原创的数学Mathematics代写服务。我们的专家在图论代写Graph Theory代写方面经验极为丰富,各种图论代写Graph Theory相关的作业也就用不着 说。

线性代数代写

线性代数是数学的一个分支,涉及线性方程,如:线性图,如:以及它们在向量空间和通过矩阵的表示。线性代数是几乎所有数学领域的核心。

博弈论代写

现代博弈论始于约翰-冯-诺伊曼(John von Neumann)提出的两人零和博弈中的混合策略均衡的观点及其证明。冯-诺依曼的原始证明使用了关于连续映射到紧凑凸集的布劳威尔定点定理,这成为博弈论和数学经济学的标准方法。在他的论文之后,1944年,他与奥斯卡-莫根斯特恩(Oskar Morgenstern)共同撰写了《游戏和经济行为理论》一书,该书考虑了几个参与者的合作游戏。这本书的第二版提供了预期效用的公理理论,使数理统计学家和经济学家能够处理不确定性下的决策。

微积分代写

微积分,最初被称为无穷小微积分或 “无穷小的微积分”,是对连续变化的数学研究,就像几何学是对形状的研究,而代数是对算术运算的概括研究一样。

它有两个主要分支,微分和积分;微分涉及瞬时变化率和曲线的斜率,而积分涉及数量的累积,以及曲线下或曲线之间的面积。这两个分支通过微积分的基本定理相互联系,它们利用了无限序列和无限级数收敛到一个明确定义的极限的基本概念 。

计量经济学代写

什么是计量经济学?

计量经济学是统计学和数学模型的定量应用,使用数据来发展理论或测试经济学中的现有假设,并根据历史数据预测未来趋势。它对现实世界的数据进行统计试验,然后将结果与被测试的理论进行比较和对比。

根据你是对测试现有理论感兴趣,还是对利用现有数据在这些观察的基础上提出新的假设感兴趣,计量经济学可以细分为两大类:理论和应用。那些经常从事这种实践的人通常被称为计量经济学家。

Matlab代写

MATLAB 是一种用于技术计算的高性能语言。它将计算、可视化和编程集成在一个易于使用的环境中,其中问题和解决方案以熟悉的数学符号表示。典型用途包括:数学和计算算法开发建模、仿真和原型制作数据分析、探索和可视化科学和工程图形应用程序开发,包括图形用户界面构建MATLAB 是一个交互式系统,其基本数据元素是一个不需要维度的数组。这使您可以解决许多技术计算问题,尤其是那些具有矩阵和向量公式的问题,而只需用 C 或 Fortran 等标量非交互式语言编写程序所需的时间的一小部分。MATLAB 名称代表矩阵实验室。MATLAB 最初的编写目的是提供对由 LINPACK 和 EISPACK 项目开发的矩阵软件的轻松访问,这两个项目共同代表了矩阵计算软件的最新技术。MATLAB 经过多年的发展,得到了许多用户的投入。在大学环境中,它是数学、工程和科学入门和高级课程的标准教学工具。在工业领域,MATLAB 是高效研究、开发和分析的首选工具。MATLAB 具有一系列称为工具箱的特定于应用程序的解决方案。对于大多数 MATLAB 用户来说非常重要,工具箱允许您学习和应用专业技术。工具箱是 MATLAB 函数(M 文件)的综合集合,可扩展 MATLAB 环境以解决特定类别的问题。可用工具箱的领域包括信号处理、控制系统、神经网络、模糊逻辑、小波、仿真等。